In the early 1980s, I was living in a squat in White Hart Lane with a painter friend, trying to put enough work together to get into Goldsmiths college. I was trying to paint, but I’d get stuck – not because I couldn’t think of anything to paint, but because there was too much possibility. My studio was in the squat and as I worked I’d hear the old guy who lived next door listening to his TV or radio. I’d see him out on the street, too. He used to walk around in big coats pushing a shopping trolley. He’d go collecting things and bring all this crap back. I found out later he was called Mr Barnes.

After being there trying to paint for a month or so, I stopped hearing anything. Thinking maybe he’d had an accident, I climbed over the back with some friends. The house was empty and derelict except for two rooms on the top floor, which had their doors locked. We broke them down and had a look around but then we felt like we shouldn’t really be there. So we contacted the council and they told us he’d been rehoused.

When I heard that, I went back to explore the place – and found 60 years of stuff. This guy was a hoarder. He had put things on his table, piling them up high. It struck me that the actual act of putting things there had become something in its own right. It was like a sculpture made with his own possessions. It obviously gave him a lot of comfort, but it was quite crazy as well.

I sort of became Mr Barnes. My studio was empty, full of blank canvases because I didn’t know what to paint, whereas his place was rammed with stuff. I spent two weeks going there day and night. I found tools, hammers, screwdrivers, saws and hand drills. I realised you could use these things to make collages, but you could also use them in collages, because they were great designs themselves. I even came across things I’d thrown out: he’d found them and taken them home. There was stuff from graveyards, too, including hands that had fallen off a sculpture.

Collage is a strange thing. It’s a French word, which annoys me – like avant garde. There’s a great quote by John Lennon: “Avant garde is French for bullshit.” But I don’t think there really is another word for collages. I’d been in a rut and they got me out of it. Now I was hyperactive. Things started happening quickly for me and I put it all down to Mr Barnes. It was like he’d started something and I’d hijacked it. One of my most successful collages, I remember, was a 1985 work called Expanded from Small Red Wheel. But I had mixed feelings: while I was creating things myself, I was also somehow cheating and getting all this stuff from Mr Barnes.

I remember being shocked by the smell when I first went into his house – this bad, human smell. A white sheet on his bed looked like black leather because there was so much dirt on it. “That’s horrible,” I thought. But after being in and out of there for a week, I grew to like the smell. It was almost as if the only way I could feel comfortable making the collages was by somehow becoming Mr Barnes.

He ended up having a much more powerful impact on me than I could have ever realised at the time. At first, I was just thinking about his stuff. Then, when I got to Goldsmiths and started learning, I realised this guy was like the ultimate conceptual artist, even though he had no connection to the art world and no audience (although maybe he did, I don’t know for sure).

I think, ultimately, everything I’ve done is collage. It has brought a reality to my work. The idea of being a painter is more desirable, but to fabricate a kind of universe entirely from scratch – I’ve always found that really difficult. Whereas taking broken elements of an existing world and rearranging them into a new universe came naturally.

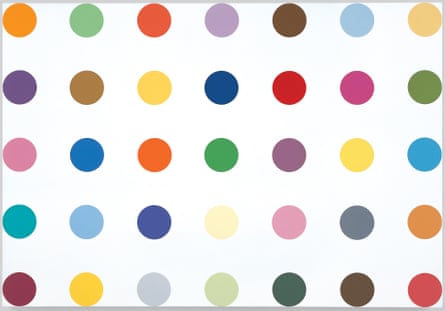

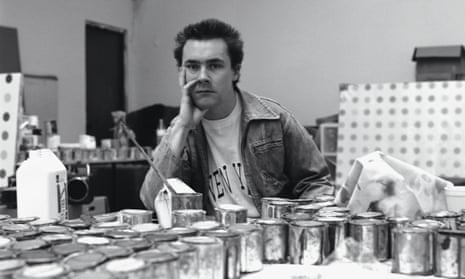

Collages led me to my first paintings, the spot paintings. I took a kind of scientific, mathematical approach and just played with colour. I remember a tutor saying they’d make nice curtain designs. It was horrible to hear that, really disheartening. But I’ve now realised that I used to get seduced by colour when I was trying to explore forms. So they were like curtain designs. And you can have really nice curtains. There’s an idea that nice curtains aren’t art, but maybe they should be.

One of the strangest things about Expanded from Small Red Wheel is that I gave it to the American artist Robert Rauschenberg as a gift. I was thinking a lot about Rauschenberg and his collages when I made it. When he died, I bought it back from his estate for my collection. I saw it recently in the studio and felt proud: it seemed tight and painterly. A lot of the other collages became trash, a bit like tissue paper left out in the rain, but this one has held together.

I find the fact that it was owned by Rauschenberg quite difficult to fathom, given that the most powerful force in it is Mr Barnes. All its elements were held much more firmly by him. I wonder about those objects, the shapes and the pieces of wood he picked up for a reason. I don’t know what those reasons were, but I too picked them up and thought: “I like this and I don’t know why.” When I look at it, I think more about Mr Barnes than I do about anything else.

I went to visit Louise Bourgeois towards the end of her life. I remember being in her house in New York and looking at the walls and seeing that they were crumbling. The light switches were very old. Everything was sort of worn and falling apart. Then I realised the same thing was happening to her. I understood that when you get older, you don’t want to live in a clean sterile environment. You actually get comfort from a place that’s ageing in the same way as you are. I remember thinking that there will be a point, as I get older, when I’m no longer turned on by cool minimal white galleries.

I’ve made a lot of work and the collages were my huge turning point. It was like one artist died and another was born. I learned a hell of a lot about form, about structure, about colour. A Hundred Years, A Thousand Years and the other works I later made with flies were another turning point. They reflected a nostalgia I was feeling for the early collages. As I got into the spot paintings, I was afraid I was becoming a minimalist – and losing some sort of emotional content, which I felt was important in art.

But after I’d finished them, I actually found that they contained emotion. I mean, when you look at works by Carl Andre, they’re emotional, they’re spiritual, they have the same thing as a Rothko or a De Kooning. They’ve got feeling, they’ve got gesture, but you don’t really realise this until you’re standing in front of them. The idea itself is devoid of feeling, but the reality is full of it. Even when you walk into a bank, there’s an emotional feeling. The world we live in is full of feelings.

One day I went to Mr Barnes’s house and the rooms were empty. The council had come round, smashed the windows with shovels and thrown everything out. And so it was two empty rooms again. I was shocked. I’d spent two weeks going through 60 years of a guy’s life and now it was all gone.

This is an edited extract from The Start, the Guardian’s new culture podcast, in which famous artists talk about their first work. Produced by Eva Krysiak, the series will also include Abi Morgan and Ai Weiwei. Go to theguardian.com/podcasts or search The Start on any podcast app.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion