Bollywood's Terrible 2017

Why the industry sputtered this year, and what it means for its future.

In December 2008, the romantic comedy Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi, starring Shah Rukh Khan and Anushka Sharma, hit theaters across India. The film, which told the story of a middle-aged man who undergoes a personality makeover to win the love of his young wife, grossed over $25 million worldwide, making it one of that year’s biggest hits. A typically glossy, over-the-top Bollywood romance was just what the country needed in the wake of the Mumbai terror attacks, which had occurred just a few weeks earlier.

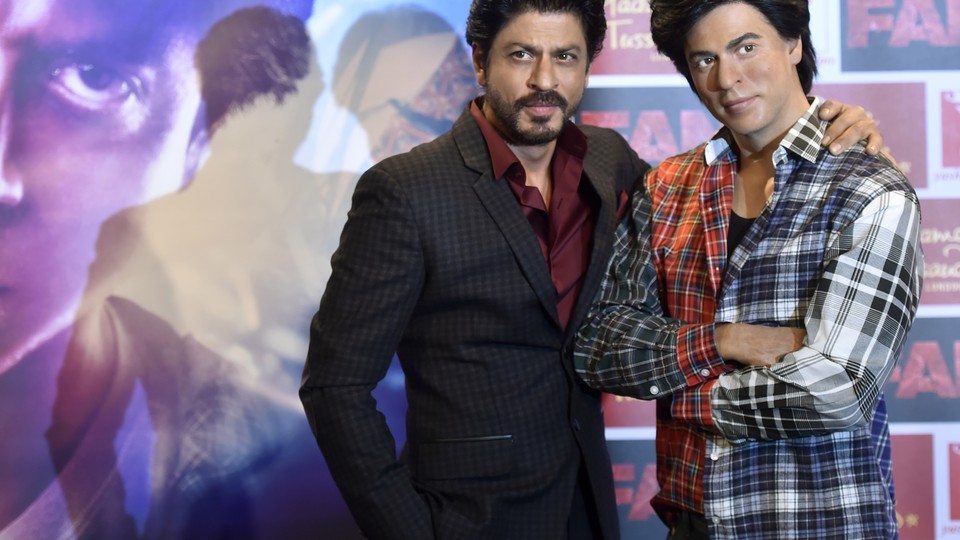

This past August, Khan and Sharma collaborated again on a romantic comedy called Jab Harry Met Sejal, about a young lawyer falling in love with her middle-aged European tour guide. Reviews were mostly negative; despite receiving a much wider release than Rab Ne Bana Di Jodi, it ranked as one of 2017’s biggest flops, netting a paltry $10 million worldwide by the end of its theatrical run. But it’s just one of a number of underperformers: Big films starring otherwise bankable stars like Shah Rukh Khan, Salman Khan, Ranbir Kapoor, and Shahid Kapur, have also tanked. “It would be a fallacy to assume this was just a bad year,” Siddharth Roy Kapur, a Bollywood film producer, told me. Jagga Jasoos, an ambitious adventure-musical he co-produced, received a smattering of encouraging reviews but is by far the biggest commercial disaster of 2017.

The very nature of Bollywood films is changing. Though big-budget films are by no means extinct, such productions are increasingly viewed as financial gambles that must compete with the wider range of high-quality options available to viewers. Even if quite a few Bollywood releases have sold more tickets by virtue of their wider releases, it’s the smaller, more critically acclaimed releases like Newton and Hindi Medium that were among 2017’s most profitable films. This apparent shift has been underway for the past decade—it’s the sense of panic gripping the industry that is new.

There are a number of potential explanations. In 2009, the domestic box-office share of films produced in Hollywood was 7.2 percent. This year through October 1, the figure was 19.8 percent, according to Box Office India, with blockbusters like The Fate Of The Furious and Thor: Ragnarok among the biggest hits in India. These films receive releases as wide as mainstream Bollywood movies. And because they’re dubbed into a number of Indian languages, including Hindi, Tamil, and Telugu, they reach more viewers than films in Hindi, which isn’t spoken as widely in the south and northeast corners of the country.

Many Indians also now prefer to consume their entertainment on streaming platforms such as Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Hotstar, whose combined subscriber base has grown 160 percent in the past year. Piracy also costs the Indian movie industry roughly $2 billion a year.

Still others eschew Hindi movies in favor of regional language films. The southern Tamil and Telugu-language film industries, which each produce nearly as many films as Bollywood, have long dominated their regions, and are beginning to capture more of the national box-office. This year, the Telugu-Tamil bilingual fantasy epic Bahubali 2: The Conclusion was far more successful than any Bollywood film; its dubbed Hindi version alone has taken in $74.8 million, while the highest-grossing Hindi film, Golmaal Again, has managed only $31.6 million.

While Bahubali 2 was praised for its imaginative storyline and inventive, CGI-driven combat sequences, Golmaal Again is regressive, formulaic, and puerile. Industry experts said that the latter’s relative success at the box-office stemmed from the fact that it had a wide release and opened during the Hindu festival of Diwali, traditionally a popular time for going to the movies. In 2017, star-led films such as Mubarakan, Haseena Parkar, Baadshaho, stumbled at the box office, while the success of Golmaal Again is being seen as an anomaly—a telling sign.

Meanwhile, the industry is banking on the “small big film” as well as web-only shows to get itself out of its ongoing creative rut. “You can’t have uniformity of taste in a country as vast and diverse as India,” Gaurav Verma, chief revenue officer at Red Chillies Entertainment, a prominent film production house, told me. “Filmmaking is a long process … and we often find that tastes have changed by [the end of a production]. The challenge is to find something that doesn’t age so easily. Also, longform [shows] helps you make challenging content on subjects you wouldn’t have touched earlier.”

In mid-November, Red Chillies announced plans to partner with Netflix on an eight-episode thriller series based on young novelist Bilal Siddiqui’s The Bard of Blood. This is the latest in a slew of upcoming shows helmed by prominent filmmakers like Anurag Kashyap, Vikramaditya Motwane,Vidhu Vinod Chopra and Vishal Bhardwaj. A few days later, it was announced that maverick producer Ronnie Screwvala would be releasing his upcoming film Love Per Square Foot as a Netflix original, making it the first mainstream Indian film to be made for a streaming platform. A week later, Roy Kapur Films announced that it would be making digital content for telecom giant Reliance Jio’s subscribers. It is no coincidence that India is projected to have half a billion smartphone and Internet users some time next year.

Mainstream Hindi cinema, often (rightly) criticized as regressive and stale, is still trying to find the right, commercially viable language for what Roy Kapur called “high-concept films with talking points.” 2017 was encouraging on that front. Verma cited this year’s Shubh Mangal Savdhan, a romantic comedy about a young groom suffering from erectile dysfunction, as an example of a recent film that balanced commercial success while pushing boundaries. “We’re a developing nation and an evolving society,” he said. “Change will take time.” (Incidentally, the film was a remake of a 2013 Tamil film made by the same director.)

Furthermore, a new production house called Yoodlee Films aims to make star-less, “content-driven” cinema the norm. It plans to release one film a month over the next seven years, made within low budgets and in adherence to a Dogme-95-esque manifesto agreed upon by all parties. “The idea is to think of the viewer as a buyer, whether they buy a movie ticket or watch [a film or show] on a VOD platform, and to create a habit that we can then fulfill with these movies,” Siddharth Anand Kumar, the company’s head, said.

While the process is underway, there are also many who feel that it’s time Bollywood stopped being synonymous with Indian cinema and became a gateway to other cinema and voices in the region—and the only way to do that is to collaborate on a deeper level, strengthening Indian cinema as a whole.

“If you look at films until the ‘60s and ‘70s, Bollywood’s strength was that it assimilated talent from different parts of the country,” Meenakshi Shedde, film critic and South Asia consultant to the Berlin and Dubai film festivals, told me. “Then, it became arrogant and lost its way. But now, as a survival strategy, it has no option but to course-correct.”