“Have you ever been pregnant?” artist Helen Maudsley asks me.

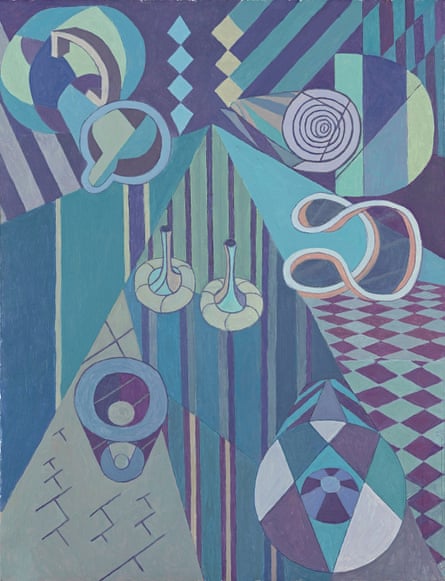

We are standing in a room papered with earthy pinks and purples, in front of a series of paintings peppered with an array of motifs – roses, columns, geometric hands, splashes of colour. Maudsley, one of Australia’s most tenacious and perhaps most underrated artists, is trying – valiantly – to help me understand her work.

“It’s the most extraordinary thing ,” she says, when I tell her that no, I haven’t ever been pregnant. “When the baby first starts to move, it’s exactly like a fish when you’re fishing. And that’s the flicker of life.”

The “flicker of life” is an element of the painting we are analysing. I know this because it is mentioned in the painting’s long and, at first blush, arbitrary title. But I struggle to see it in the work itself until Maudsley points out particular flecks of red paint.

We are down the hall from Del Kathryn Barton’s psychedelic, multi-roomed new exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria. The space dedicated to Maudsley’s Our Knowing and Not Knowing, the 90-year-old’s solo exhibition, is far smaller than that of her fellow artist – one room, to be precise. The tone might be much more muted, but there’s still a lot going on.

The 30 paintings and drawings housed here represent an intense five years of work for Maudsley, who features in a suite of five solo exhibitions for NGV Australia’s summer program. An artist who began her formal training at the National Gallery of Victoria Art School (now the Victorian College of the Arts) in the 1940s, and has been practicing daily for some 70 years, Maudsley is frank about the fact that her career has been “low status”. She is similarly upfront about the difficulty of being a modernist painter working in an era in which the traditional boundaries between artistic forms have collapsed.

“I don’t know what the contemporary art world is now because it’s nothing to do with painting,” Maudsley says. “It’s all got so muddled up, the categories have gone, I think. Mostly now there’s very little interest in painting.”

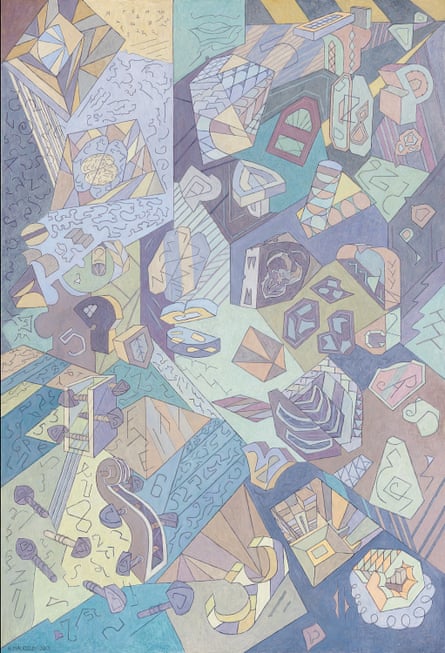

Maudsley’s work comes across like a puzzle – a series of symbols with cultural resonance, laid out with specific intention. The titles are keys – hints to the viewer to guide them in their understanding of the piece.

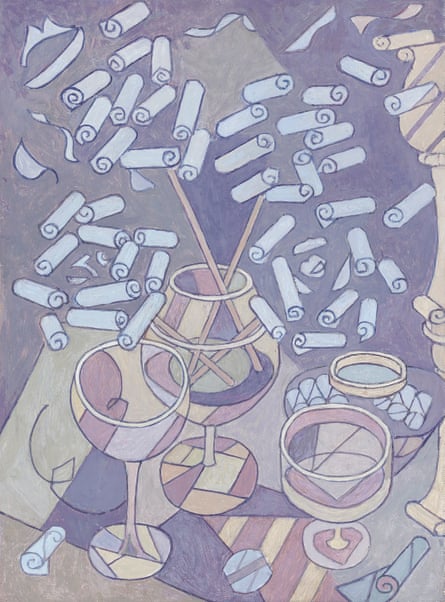

Maudsley leads me over to a painting titled “4 Roses in a Vase. 4 Heads and One Face. 4 People and the Golden Pillar.”

“You see, it’s one rose in a glass – a bunch of roses in the glass, but each rose is slightly different,” she says. “The formation is a round head and the face is the glass. It’s a glass with the roses; it’s a head; but it’s also four heads because all the roses are different.”

“So, the scrolls are roses?” I say, somewhat stupidly.

“Of course,” says Maudsley. “If you stare at a rose, that’s what it is.”

“I had not thought of it like that.”

“No, well, you don’t,” she says. “You stare at it. And when you stare at the roses, the scrolls are perfect.”

If this seems cryptic, it’s because Maudsley’s work isn’t intended to be understood at first glance. She values her audiences putting in effort. “The energy that it takes to try and hear what somebody is saying, that’s the virtue,” she says. “It’s not an intellectual thing; it’s the act of trying to hear what’s being said.”

“These are really her reflections on social dynamics around her,” says curator Pip Wallis. “They use visual language – so forms, shapes, and associations with those shapes – to tell a story.”

What might initially appear to be a jumbled or hallucinogenic assortment of arbitrary images is, says Wallis, a very specific composition, with Maudsley drawing on the history of western art in her choice of symbols. But despite the abstract nature of the work, Maudsley is very clear that she is not interested in expressing the unconscious, or channelling dreams.

“I’ve always thought of myself as a realist,” she says. “Although I don’t think other people have ever seen it like that. But I’m trying to identify what I see. But the issue is – what is it that you’re seeing?”

Maudsley calls her paintings “visual essays” – a term that is more illuminating if you think of an essay as a focused, methodical attempt to explore a concept. A number of works in Our Knowing and Not Knowing, for example, are partly an attempt to pick apart the idea of “feral”, which she describes as the sudden appearance of aggression between people. The process of creating the works – technical, detailed and time consuming, involving many drafts – is also a process of working through the idea for herself.

Maudsley’s art, accordingly, is not well-served by the high-speed Instagram-and-move-on approach to gallery visits. The paintings need to be sat with, contemplated, considered.

The wife of acclaimed painter of modern urban Australian life, John Brack, Maudsley remembers the era in which she and her peers came of age as artists to be one full of cliques and conflict.

“Honestly, when we were growing up in the 1940s and 50s, art was like a lot of territories, a lot of fiefdoms, with everybody fighting each other. Nobody would talk to each other. It was hideous.

“It was [art patron and Heide founder] John Reed – he was king of the kids,” she says. “They all just stood there and fought each other. It wasn’t a community of goodwill.”

Once an artist has been defined by a culture, they can’t be redefined, Maudsley says. The influence of art historian Bernard Smith’s seminal text, Place, Taste and Tradition: A Study of Australian Art since 1788, for instance, has been profound – not only on what are considered the key works in Australian art history, but also because its publication cemented the careers of a select number of working artists at the time.

“If you were in Bernard’s book you had your career made because that passes down, you see. But what’s amazing to me is that Bernard’s book, even 10 years ago, was referred to endlessly as if it was a primary source.”

The artwork itself – that is the primary source, she says. She worries particularly that art students and writers rely too heavily on the words of others in their assessment and understanding of art, rather than listening to the work itself.

“You have to learn to do what the picture tells you,” Maudsley says, a trick she learnt from spending time with the work of 15th century painter Jan van Eyck.

“I think the grammar of art is terribly important but you need to know it. The fact that things call to each other and move around and so on. And you find that in the art of the past,” she says.

“It’s visual analogy, really. I use the grammar of visual analogy, which I didn’t invent – it’s an ancient thing.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion