The Brutal Math of Gender Inequality in Hollywood

Of the top 250 films of 2017, 88 percent had no female directors, 83 percent had no female writers, and 96 percent had no female cinematographers.

The Golden Globe Awards on Sunday provided a useful snapshot of the limitations of the #MeToo movement. Viewers gazed into a monochromatic protest against the scourge of harassment, with uniformly black dresses and suits, “Time’s Up” pins, and often inspiring speeches about standing up to abusive power.

But while host Seth Meyers filleted Hollywood’s most infamous offenders and Oprah Winfrey brought the audience to its feet with a rousing address, the brutal math of inequality lurked beyond the telecast. Lady Bird won the award for Best Motion Picture Musical or Comedy, but its writer and director Greta Gerwig was curiously not nominated for Best Director. That category’s five nominees were all male. In fact, only one woman has ever won a Golden Globe for directing: Barbra Streisand, in 1984, for Yentl. At the time, Gerwig was six months old, and her film’s lead actress had not yet been born. Hollywood remains an industry where women are more likely to be celebrated for speaking out in front of a camera than for holding one.

The numbers are staggering: Of the top 250 films of 2017, 88 percent had no female directors, according to the most recent “Celluloid Ceiling” report from San Diego State University. What’s more, 83 percent of the films had no female writers, and 96 percent had no female cinematographers. According to earlier versions of the survey, more than 90 percent of major studio films have no female assistants on set, including gaffers, key grips, or supervising sound editors.

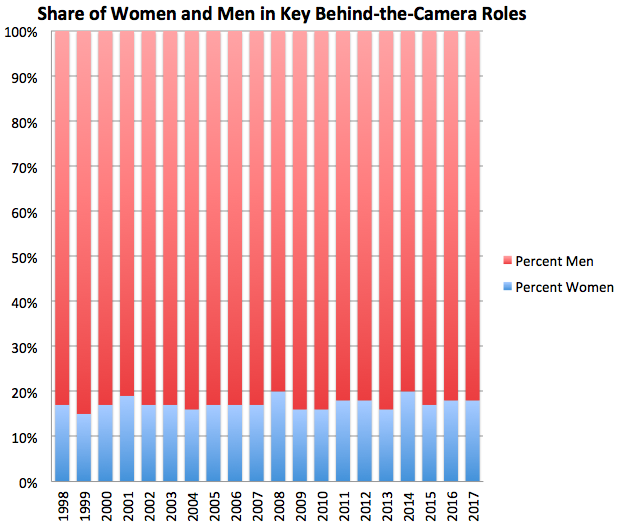

The report has tracked women’s employment in top-grossing films for 20 years. “In 2017, women comprised 18 percent of all directors, writers, producers, executive producers, editors, and cinematographers working on the top 250 domestic grossing films,” wrote Martha Lauzen, the author of the report and a professor of film and television at San Diego State University. In the last two decades, the gender wage gap in America has narrowed and women have eclipsed men in the ranks of new college graduates. But behind the camera in Hollywood, nothing has changed since the late 1990s.

The emphasis on accused celebrities like Harvey Weinstein and Kevin Spacey is appropriate, but brutish behavior against women emerges naturally from a industry that deprives most of them from the power to produce, direct, write, or film. Sociological studies on sexual harassment have shown that the worst industries for harassment combine several factors: male domination in positions of power; work arrangements that are relatively transient; and young, single women in more-vulnerable and low-paying occupations.

All three descriptors apply to the movie business. First, men clearly outnumber women four-to-one among producers, directors, cinematographers, writers, and key assistants. Second, every movie or miniseries is essentially a miniature start-up, where predators and jerks can abuse or harass actors and assistants knowing they might never have to work them again after a three-month shoot.

Finally, actresses are vulnerable, not only because men dominate powerful occupations, but also because women are cast to portray the very quality of vulnerability. In my book, I reported on a study by the Geena Davis Foundation that analyzed speaking roles in 120 popular films released between 2010 and 2013 for demographics, sexualization, occupation, and career. Just 23 percent of these films had a girl or woman as a main character. The ratio of men to women portrayed at the highest levels of local or national government authority was 115-to-12 (and three of the 12 female roles were portrayals of one person: Margaret Thatcher). Meanwhile, girls and women were twice as likely as boys and men to be shown in sexually revealing clothing, and five times more likely to be called out for being attractive. If these movies collectively formed a single nation, women in this world would account for less than one-third of the workforce and two-thirds of its sex workers.

Altogether, these surveys and studies suggest something quite simple: The ratio of women in an industry (like film) or in an occupation within that industry (like directing) shapes how women are treated. While more than 80 percent of women say they have been harassed at work, they are 50 percent more likely to say so in male-dominated industries.

In Hollywood, as in media or any industry dominated by powerful men, it is important yet insufficient to name, shame, and expel the worst offenders. More fundamentally, it is critical to address the sheer number of women who work in the industry in positions of authority. Black dresses and pins get people talking. But in the end, it’ll be the math that matters.