The President Who Doesn’t Read

Trump’s allergy to the written word and his reliance on oral communication have proven liabilities in office.

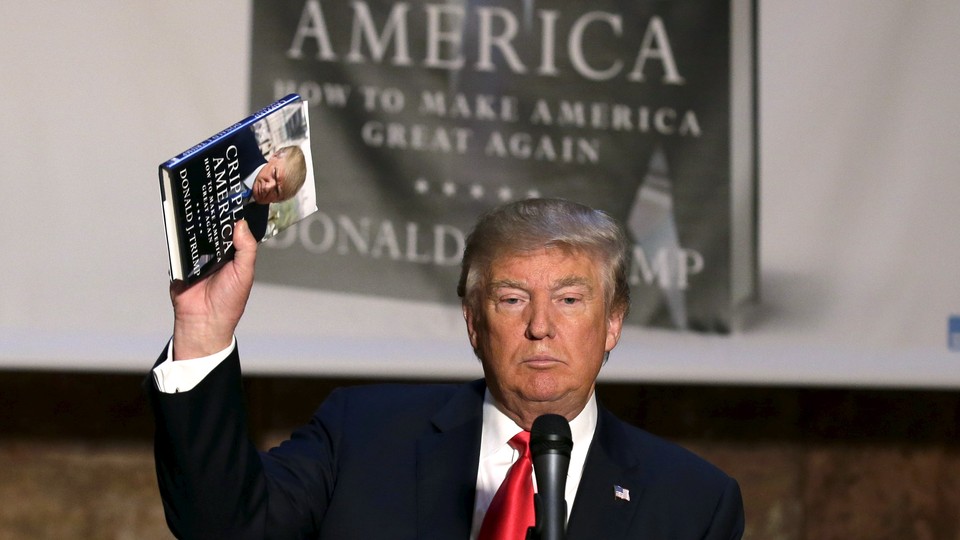

Ironically, it was the publication of a book this week that crystallized the reality of just how little Donald Trump reads. While, like many of the tendencies described in Michael Wolff’s Fire and Fury, Trump’s indifference to the printed word has been apparent for some time, the depth and implications of Trump’s strong preference for oral communication over the written word demand closer examination.

“He didn’t process information in any conventional sense,” Wolff writes. “He didn’t read. He didn’t really even skim. Some believed that for all practical purposes he was no more than semi-literate.”

Wolff quotes economic adviser Gary Cohn writing in an email: “It’s worse than you can imagine … Trump won’t read anything—not one-page memos, not the brief policy papers, nothing. He gets up halfway through meetings with world leaders because he is bored.”

While Trump and his allies, as well as some mainstream journalists, have attacked the accuracy of Wolff’s book, Trump’s allergy to reading is among the most fully corroborated assertions Fire and Fury makes.

Ahead of the election, the editors of this magazine wrote that the Republican candidate “appears not to read.” Before the inauguration, Trump told Axios, “I like bullets or I like as little as possible. I don’t need, you know, 200-page reports on something that can be handled on a page. That I can tell you.” In February, The New York Times reported that National Security Council members had been instructed to keep policy papers to a single page and include lots of graphics and maps. Mother Jones reviewed classified information indicating Trump’s briefings were a quarter as long as Barack Obama’s.

In March, Reuters reported that briefers had strategically placed the president’s name in as many paragraphs of briefing documents as possible so as to attract his fickle attention. In September, the Associated Press reported that top aides had decided the president needed a crash course on America’s role in the world and arranged a 90-minute, map-and-chart-heavy lecture at the Pentagon. And amid the hype over Wolff’s book, MSNBC host Joe Scarborough wrote a column Friday saying that in September 2015, he confronted Trump over poor debate performances, saying, “Can you read?” Met with silence, Scarborough pressed again: “I’m serious, Donald. Do you read? If someone wrote you a one-page paper on a policy, could you read it?” Trump replied by brandishing a Bible from his mother and saying he read it all the time—probably a self-aware joke, given Trump’s proud impiety and displayed ignorance of the Bible.

The Scarborough anecdote is the strangest of these. This is not only because Scarborough held on to the story for nearly a year and a half, and continued to hype Trump’s candidacy on air and advise him privately. (As James Fallows notes, the real scandal of the Wolff book is that so many people have such grave misgivings about Trump but have kept their heads down.) It is also unfortunate because Trump is clearly, in strictly literal terms, literate. He displays his basic grasp of the language—if in sloppy, often typo-ridden ways—on Twitter on a roughly daily basis. Such stories, by dint of their hyperbole, offer a bit of a distraction from how serious the problem is.

Meanwhile, Trump’s defenders could fall back on semi-plausible excuses, such as arguing that his information consumption was typical of the business world from which he had come. The AP reported that Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and Secretary of Defense James Mattis used charts and maps in the briefing on America’s role because that was “a way the businessman-turned-politician would appreciate.”

There was some precedent for this. Bill Clinton famously loved long briefings, to the point that aides became frustrated with his tendency to focus too much attention on minutiae and lose the big picture. But although Barack Obama also liked briefings on the longer side—three-to-six page policy papers, and lengthy president’s daily brief—he asked aides to present memos demanding a decision to him with his options distilled in checkboxes at the end.

George W. Bush, who came from a business background—he attended Harvard Business School, and would eventually borrow biz-school jargon for the title of his memoir Decision Points—was closer still to Trump’s approach. Bush wanted an oral briefing to accompany the written PDB, and his PDB was slimmed down to no more than 10 pages, according to Philip Shenon. In another augur of Trump, Ron Suskind reported that aides observed that whatever was in the final verbal briefing Bush received usually became his view.

Yet the differences between this and Trump are significant, one of the many ways that Trump has made Bush’s critics feel nostalgic for him. Critics mocked or rent their garments over Bush’s abbreviated brief, but Trump’s preferred format is far shorter and more rudimentary. Besides, the Bush precedent is not comforting for anyone concerned about a steady hand on the wheel of the ship of state: The Iraq War remains the greatest blunder in American foreign policy since Vietnam, and Trump has expressed puzzlement about the seemingly unwinnable war in Afghanistan that Bush bequeathed him via Obama.

Unlike Trump, Bush also read for pleasure and edification. Late in Bush’s presidency, Karl Rove wrote a notable column in which he detailed the president’s reading habits. At the time, Richard Cohen described Bush’s list as too closed to critical ideas: “Bush has always been the captive of fixed ideas. His books just support that.” Such a critique of Trump is unthinkable, because the idea of him recommending any volume that is not either by him or a hagiography of him is unthinkable. One can deride the reading of Bush and Obama—who last week continued a tradition he began as president, posting his reading list for the year—as performative, but Trump, a consummate performer in so many other respects, cannot even be bothered to perform here.

There’s been plenty of attention paid to Trump’s excessive (and implausibly denied) television watching, but it’s really more of a piece with his broader orientation away from the written word and toward oral culture. The president likes verbal briefings, phone conversations, and television because they’re all conducted aloud, sans reading. Wolff writes:

If he was not having his 6:30 dinner with Steve Bannon, then, more to his liking, he was in bed by that time with a cheeseburger, watching his three screens and making phone calls—the phone was his true contact point with the world—to a small group of friends, who charted his rising and falling levels of agitation through the evening and then compared notes with one another.

Trump has always loved the telephone: Stories of him calling business associates and friends, or reporters, whether under his own name or pseudonyms, litter his business career. (There are limitations, Wolff suggests: Aides found that Trump “could not really converse, not in the sense of sharing information, or of a balanced back-and-forth conversation.”) His conversations with friends are a crucial source of information and pressure release. Shortly after taking office, per the Times, Trump told a friend, “I can invite anyone for dinner, and they will come!” The ability to invite—and one presumes call—anyone and have them reply flatters Trump’s ego and seems to be one of the few parts of his position that he enjoys.

In view of this oral fixation, Trump’s affection for Twitter is not as paradoxical as it seems. It requires only 140, and now 280, characters at a time; is often fed by what he’s watching on TV; and it is only outgoing: The president need not read himself to tweet effectively. The conversationality of Twitter fits his M.O. too. While Trump is billed as the author of many books, it’s clear he didn’t actually write them. Art of the Deal ghostwriter Tony Schwartz savaged him during the campaign, while Trump has blamed errors in other books on mysterious speechwriter Meredith McIver. It’s not like these books are great literary achievements, anyway. What Trump imparts to them is his conversational shtick. Unlike past presidents, there’s little evidence of a written record of letters or other correspondence, either. The paradigmatic Trump epistle is a cease-and-desist letter from counsel.

Trump’s particular affection for television is notable. As a Baby Boomer, he is a member of a generation raised on television and still especially fond of it. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, people in Trump’s age cohort watch an average of four hours of television a day, meaning his reported four-to-eight-hour habit is only somewhat greater than the norm. But that demographic also spends the most leisure time reading—almost an hour a day, per the BLS, by far the greatest of any age group.

There’s a reason so many 65-to-74-year-olds read a lot: Many of them are retired, and don’t have to do work. Trump, by contrast, has one of the most demanding jobs in the world. One reason that it’s demanding, however, is that the holder is expected to consume, digest, and absorb prodigious amounts of information via reading, and there’s little to suggest that Trump is doing that. Instead, he has taken that time up with phone conversations, television, and golf, another forum for oral communication. (Per Philip Bump, Trump played golf every 4.7 days in 2017, good for 10 full 24-hour days and far higher than Obama’s rate as president.)

Trump denies this, of course. “All my life I’ve heard that decisions are much different when you sit behind the desk in the Oval Office—in other words, when you’re president of the United States,” he said earlier this year. “So I studied Afghanistan in great detail and from every conceivable angle.”

The president’s actions show little such sign of preparation and study, while displaying faulty understandings of many things. After visiting Saudi Arabia and hitting it off with the country’s leaders, he forcefully backed Riyadh in its dispute with Qatar and many other issues, over the objections of some of his staff—even publicly contradicting Tillerson. In December, however, he suddenly became concerned about the humanitarian crisis in Yemen. The minimal thought put into several of Trump’s core views on China became clear when President Xi Jinping was able to change his entire view of the Korean incident in 10 minutes—10 minutes of oral conversation, of course.

Then there was his more recent decision to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel and move the U.S. Embassy there. That decision was controversial but not without defenders, and the U.S. insisted the move did not settle the final status of Jerusalem in peace talks with the Palestinians. Apparently Trump did not get (or perhaps did not read) the memo, because in a tweet earlier this week he said that the U.S. had “taken Jerusalem, the toughest part of the negotiation, off the table,” rattling both Israelis and Palestinians.

The refusal to read, and the resulting limits of Trump’s understanding of complicated issues, doesn’t mean that every decision he makes is bad. Indeed, it can be liberating—allowing him to act on instinct, even in the face of expert reservations. My colleague Krishnadev Calamur, for example, writes that the anger that led the White House to freeze aid to Pakistan this week is understandable. But the shaky grasp of the underlying currents means Trump is more likely to blunder on any given case, and Trump’s misstatements and missteps earn him mockery and undermine his stature around the world.

Perhaps no single area better summarizes Trump’s strange tendency than his press shop. He was reportedly driven to distraction by Press Secretary Sean Spicer’s ill-fitting suits and bumbling demeanor, and eventually Spicer was pushed out in favor of Sarah Sanders, a calmer and more commanding force in the Brady Room. But in its written work, the White House press team continues to commit errors and gaffes and issue typo-flecked statements.

While most problems faced by presidential administrations are incredibly complex, the solution to problems caused by a president who does not read is fairly simple: He ought to start reading. Simple and easy are very different matters, though, and expecting a man who has always preferred chatting and watching television to the printed word to become a reader at 71 would be foolish. There’s no Trump pivot, especially not to the bookshelf.