Prepare for the New Paywall Era

Digital media’s free-for-all days are ending, but will the new strategy work?

If the recent numbers are any indication, there is a bloodbath in digital media this year. Publishers big and small are coming up short on advertising revenue, even if they are long on traffic.

The theory of digital publishing has long been that because people are spending more time reading and watching stories on the internet than other places, eventually the ad revenue would follow them from other media types. People now spend more than 5.5 hours a day with digital media, including three hours on their phones alone.

The theory wasn’t wrong. Ad dollars have followed eyeballs. In 2016, internet-ad revenue grew to almost $75 billion, pretty evenly split between ads that run on computers (desktop) and ads that run on phones (mobile). But advertising to people on computers is roughly at the level it was in 2013. That is to say, all the recent growth has been on mobile devices. And on mobile, Facebook and Google have eaten almost all that new pie. These two companies are making more and more money. Everyone else is trying to survive.

In a print newspaper or a broadcast television station, the content and the distribution of that content are integrated. The big tech platforms split this marriage, doing the distribution for most digital content through Google searches and the Facebook News Feed. And they’ve taken most of the money: They’ve “captured the value” of the content at the distribution level. Media companies have no real alternative, nor do they have competitive advertising products to the targeting and scale that Facebook and Google can offer. Facebook and Google need content, but it’s all fungible. The recap of a huge investigative blockbuster is just as valuable to Google News as an investigative blockbuster itself. The former might have taken months and costs tens of thousands of dollars, the latter a few hours and the cost of a young journalist’s time.

That’s led many people, including my colleague Derek Thompson, to the conclusion that supporting rigorous journalism requires some sort of direct financial relationship between publications and readers. Right now, the preferred method is the paywall.

The New York Times has one. The Washington Post has one. The Financial Times has one. The Wall Street Journal has one. The New Yorker has one. Wired just announced they’d be building one. The Atlantic, too, uses a paywall if readers have an ad blocker installed (in addition to the awesome Masthead member program, which you should sign up for).

Many of these efforts have been successful. Publications have figured out how to create the right kinds of porosity for their sites, allowing enough people in to drive scale, but extracting more revenue per reader than advertising could provide.

Paywalls are not a new idea. The Atlantic previously had a different one for a while in the mid-’00s. The Adweek article announcing that this paywall was being pulled down is a fascinating time capsule. Paywalls, back then, were often seen as a way of protecting the existing print businesses.

“Despite worries that putting a print magazine’s full content online for free will erode the subscriber base, nothing could be further from the truth,” wrote Adweek. “Subscribers largely obtain magazines for advantages that can be garnered only from the print version (portability, ease of use); those looking only for free articles to read can easily look at websites that offer similar content instead.”

The idea that the paid revenue from a site itself could contribute to earnings in a meaningful way was not even considered. And that made sense. The scale of most magazine sites was tiny.

“In 2007, TheAtlantic.com tripled its traffic to 1.5 million unique users and 8 million page views,” Adweek continued. “During that period, digital ad sales grew to 10 percent of total ad sales, and traffic has grown faster than The Atlantic’s digital-marketing investment.”

The first time around, many paywalls simply did not work. But times have changed. The New York Times’ success in transforming itself into a company that is markedly less dependent on advertising than it has been in recent years has emboldened many other publishers. The Times now makes more than 20 percent of its revenue on digital-only subscriptions, a number which has been growing quickly. In absolute terms, last quarter, the Times made $85.7 million from these digital products.

The question is: Can media organizations that are not huge like the Times or The Washington Post, or business-focused like the Financial Times or The Wall Street Journal, create meaningful businesses from their paywalls?

Here’s the optimistic case that they can.

For one, many digital-media properties have much larger audiences than they used to. The Atlantic had 42.3 million visitors in May. It’s hard for sites to capture the value of that whole audience with advertising alone, especially because traffic can be spiky. But in marketing terms, that whole audience is just the top of the funnel. And that’s a big funnel. Let’s say that 1 percent of visitors to The Atlantic’s site subscribed for $10 a month. (I’m not privy to conversations about pricing. I’m just making this up.) Do the math: That’s $50 million a year, which would be very significant for the magazine’s business.

It’s not just the difference in scale for different media properties, though. The reigning ideology of the internet has broken apart. In the wild days of the ’00s, paywalls were seen as breaking the way the web worked, with sites linking to each other to build on the knowledge we were collectively producing. As it turns out, the culture of links fell apart as digital journalism became more focused on traditional sections publishing individual stories and not blogs that linked to each other frequently. The rise of platform-specific video and the dominance of Facebook finished off the web as it was known in the ’00s.

Today’s intentionally porous paywalls, too, keep information flowing, even as they help companies capture subscribers.

The infrastructure for buying stuff on the internet also has gotten a lot better. There are the different payment platforms like PayPal and ApplePay. There are initiatives at Apple and Facebook to make it easier to sell subscriptions. There is the mere fact that people buy tons of stuff on their phones now, and have become increasingly comfortable with the idea of paying for content. (Thanks, New York Times!)

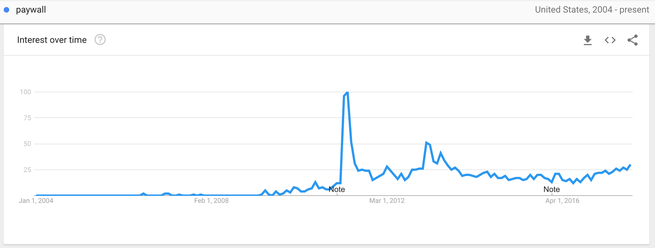

When the paywall was first introduced in early 2011, people flocked to Google to search for the term. It just wasn’t a familiar idea.

Six years later, this way of charging people for websites is no longer unusual. People may not always love them, but they know the deal.

Smaller magazines may be able to use the same digital-marketing tools to drive subscriptions in the way that other “lifestyle” brands have. One reason that Facebook has grown so quickly is that it has proven to be a very effective machine for putting in marketing dollars and getting out revenue. In the ’00s, or even five years ago, it would have been very difficult to target ads at readers except on one’s own site. Now, all the targeting tools that have made the digital-advertising business more difficult for publications can help the paid-content business.

A lot of questions remain, however, especially as more publications turn to paywalls. The group of people who pay for any kind of journalism is still relatively small. Based on the current numbers of subscribers to the big publications, we’re probably talking a group of people that numbers in the single-digit millions. That’s the addressable market.

So, as more and more publications try to woo these particular consumers, how will they split up their dollars? How annoyed will subscribers become remembering another half dozen passwords? If everyone goes all-in on paywalls, who would make your list?

Maybe the whole model of single sites running their own paywalls will not carry the day. Somebody is going to try to make the process of accessing this paid content easier and cheaper, whether it’s Apple, Flipboard, Facebook, or a new entrant.

So, expect lots of paid-content experiments, many taking the form of paywalls, but there’ll be everything from apps to merch to live events. Digital media has lived and died with advertising, but now it’s mostly just dying.