The Surprising Evolution of Dinosaur Drawings

Since the 1800s, paleoartists have tried to imagine what prehistoric creatures looked like—with wildly different results.

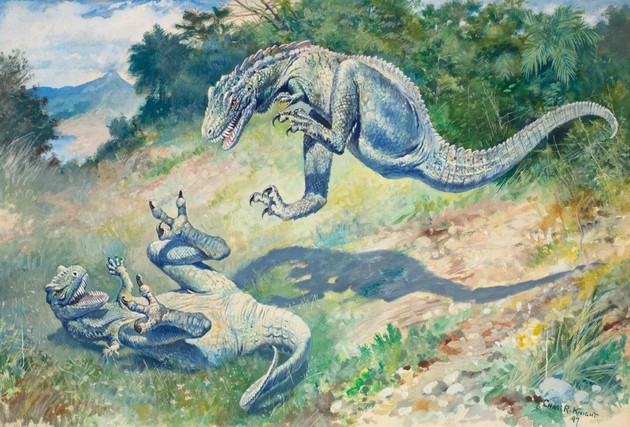

Many people visit the fossil hall at Chicago’s Field Museum for the dinosaurs; but a certain kind of art lover goes for the murals. Originally painted by the famed wildlife artist Charles R. Knight in the late 1920s, each of the hall’s 28 murals presents an elegantly composed moment in time: armored squid tossed onto a desolate Ordovician beach, a duel between Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops, saber-toothed cats snarling at flocks of giant vulture-like Teratornis. There’s a dreamy quality to the images, impressionistic landscapes blending with vibrant animal figures. It doesn’t quite matter that the renderings are now scientifically out of date; they’re convincingly alive.

Such works of paleoart—a genre that uses fossil evidence to reconstruct vanished worlds—directly shape the way humans imagine the distant past. It’s an easy form to define but a tricky one to work in. Paleontological accuracy is a moving target, with the posture and life appearance of fossil species constantly reshuffled by new discoveries and scientific arguments. Old ideas can linger long after researchers have moved on, while some artists’ wild speculations are proved correct decades after the fact. Depictions of extinct animals exist in the gap between the knowable and the unknowable, and two recent books, Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past and Dinosaur Art II: The Cutting Edge of Paleoart, probe the different ways creators have tried to bridge that divide.

As The Atlantic’s Ross Andersen wrote in a piece about paleoart in 2015, “To contemplate a dinosaur is to slip from the present, to travel in time, deep into the past, to see the Earth as it was tens, if not hundreds, of millions of years ago.” Paleoart, published by Taschen this fall, is primarily focused on how this past appeared to artists starting in the 19th century, when the genre first took root. A lavishly reproduced gallery of 160 years of prehistory-themed art, the book includes a series of short contextual essays from its author, the journalist Zoë Lescaze. Many of the animals presented in Paleoart may look odd to the modern eye: bloated, skeletal, or dragging their tails in the scientific fashion of the time. Lescaze doesn’t spend much time reflecting on the changing paleontological ideas that informed the drawings and paintings, though. “I came at the artwork through a more cultural lens,” Lescaze told me. “How they might reflect the political events of that period, or events in that artist’s own personal biography, and other techniques that any art historian would bring to a work of fine art.”

The oldest entries in the genre, in particular, illuminate how paleoart can reflect both political and aesthetic movements, Lescaze said. The first formal reconstructions of extinct animals appeared in the 1800s, around the time the first Mesozoic fossils came under scientific study. Europe was in tumult, with empires wrangling over colonial territory, and discoveries around biodiversity, extinction, and evolution were coming at a blinding pace. As such, reconstructions often took on an allegorical cast. The French artist Édouard Riou depicted marine reptiles such as Plesiosaurus and Ichthyosaurus squaring off like warships on the high seas, perhaps reacting to the naval battles of the Napoleonic wars, according to Lescaze. In the apocalyptic watercolors of John Martin, nightmarish beasts writhed and flailed in the antediluvian ooze. The artist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins thrilled Victorian Britain with paintings and sculptures of dinosaurs presiding as regal monarchs over tropical kingdoms full of lesser reptiles.

But paleoart didn’t really come into its own until the arrival of Knight. An American painter who began his career in the late 19th century and reached his peak in the early 20th, Knight worked closely with scientists such as Henry Fairfield Osborn and Barnum Brown to portray his subjects as accurately as possible, given the assumptions at the time. (In keeping with Osborn’s ideas, Knight gave his dinosaurs reedy, lizardy limbs, rather than the beefy, bird-like legs the fossils actually suggested.) Nearly blind by the time he was in his 30s, Knight opted for a naturalistic style full of heft and movement, with complementary colors, soft palettes, and expansive scenery. By Knight’s death in 1953, Lescaze said, his creations had directly influenced films like King Kong and Fantasia, writers such as Ray Bradbury, and a plethora of young paleontologists and artists.

During Knight’s life—and for some time afterward—paleoart remained a fairly loose field. Painters came from an assortment of backgrounds; some were trained illustrators, and others were enthusiastic amateurs. While they adhered to the larger paleontological views of the time, not everyone was necessarily concerned with anatomical rigor. In the 1930s and ’40s, European artists like Mathurin Méheut sought romance in prehistory with Art Nouveau designs and evocative watercolors, setting his bat-winged pterodactyls and drooping long-necked dinosaurs among asymmetrical arabesques. The Soviet paleontologist Konstantin Konstantinovich Flyorov (a great fan of Knight’s, Lescaze said) escaped the enforced artistic realism of the USSR by depicting the ancient world as a series of off-kilter fairy tales filled with dragon-like dinosaurs.

Toward the end of the 20th century, however, overt metaphor and experimentation were largely replaced by rehashes of Knight’s style, and artists drifted further away from the genre’s scientific underpinnings. The majority of those illustrating extinct animals were commercial artists without much knowledge of paleontology. A lack of accurate references encouraged large amounts of plagiarism; any one artist’s whim—a pose, a speculative anatomical detail—often became the de rigueur way of picturing an animal for decades afterward. (Knight’s dinosaurs, for example, have had a long and productive career in books, in movies, and on lunch boxes since his death.) There were exceptions, Lescaze said, such as the moody forests and skeletal dinosaurs that Ely Kish began painting in the 1970s. Paleoart ends its survey with her work. In doing so, it misses out on one of the most transformative periods in the genre’s history.

* * *

A major reassessment of dinosaurs that began in the 1960s, and finally took hold in the 1980s, positioned them not as dull evolutionary failures but as active, warm-blooded animals. Researcher-illustrators like Gregory Paul and painters like Mark Hallett began developing a rigorous anatomical style in accordance with new findings, slimming their animals down to lean creations of muscle and bone. In 1993, Jurassic Park tapped into this momentum, setting a new baseline for what dinosaurs should look like and sparking a popular craze that never quite faded.

The internet had a fundamental effect on paleoart, too. It became easier to find technical information on prehistoric animals’ anatomy, or the latest theories about their behavior. Image-hosting sites like DeviantArt, curated websites like The Dinosauricon, and dedicated blogs served as hubs for a growing paleoart community. Email listservs and the rise of social media meant researchers, professional artists, and amateurs could collaborate with each other on a wider scale. The field, in the 2010s, has become more accessible, accurate, and forward-looking than ever before—as well as more stylistically constrained.

Dinosaur Art II: The Cutting Edge of Paleoart is a dispatch from this internet age of paleontology, and is in some ways a revealing companion to Taschen’s Paleoart. Published in October by Titan Books, it compiles in-depth interviews and curated work from modern paleoartists across the globe, as collected by Steve White, a U.K. comics artist. (The book is a sequel to 2012’s Dinosaur Art: The World’s Greatest Paleoart.) Some of the featured illustrators, like Brazil’s Julio Lacerda, create digital images that look like photographic collages, while the artist Andrey Atuchin works in a clean, detailed style akin to that of classic National Geographic drawings. All the animals in Dinosaur Art II conform closely to modern scientific convention; most of the profiled artists work in the hyper-realistic mode that has come to define the genre. Compared to the breadth of approaches contained within Lescaze’s book, the results can look a little standardized and tame.

Today, the field is seeing a growing tension between a more cautious approach to paleoart and an urge for experimentation. In an attempt to make paleoart more academically credible, artists of the last few decades have often emphasized skeletal fidelity over all else. This proved to be a bit of an overcorrection: Compare a cat skull and a living cat, and it’s easy to see that skeletons aren’t always a good reflection of an animal’s flesh-and-blood appearance. Dinosaurs and prehistoric reptiles illustrated in the modern era have a tendency to look like skin shrink-wrapped over bone. A certain amount of cultural inertia and cliché also lingers, even in more carefully reconstructed art. Predatory dinosaurs in particular are still often depicted in relentless battle, mouths open in frozen roars.

In the 2010s, paleontologists and artists have been pushing for more radically imaginative approaches to soft-tissue anatomy and behavior, and less reliance on standard tropes. The “All Yesterdays” campaign—named after a provocative paleoart book published in 2012—challenged artists to think more broadly about prehistoric animals as living creatures, with sleep habits, social interactions, and foraging behaviors. All Yesterdays–style dinosaurs might have humps, or extravagant inflatable sacs, or unsuspected feathers. “There’s a nihilistic aspect to [the movement],” Mark Witton, a British paleontologist and one of the artists in Dinosaur Art II, told me. “We don’t really know what’s right or wrong about our [soft-tissue] reconstructions, so we might as well be as bold with them as our science will allow. … It’s more just about being honest, and exploring many possible truths rather than one tried-and-tested take on a subject species.”

Only traces of this new approach appear in Dinosaur Art II. Artists like Brian Engh, David Orr, and Rebecca Groom are exploring a wider range of styles, including conscious homage, fine art, and Pixar-inflected designs. As long as the art is grounded by a scientific understanding of the animal in question, Witton said, there’s still a lot of room for inventiveness. “Certain styles distort reality by necessity, so if we simplify the form of our subjects into basic geometries … or apply surreal color palettes, are we still making paleoart?” Witton asked. “We’re still scratching the surface of paleoart’s potential diversity.”

* * *

While paleoart is a form of scientific art, its value doesn’t always lie in its level of accuracy. According to Lescaze, while researching Paleoart, she met a Smithsonian paleontologist who showed her an original Knight dinosaur painting he had in his office. He’d fished it out of a dumpster after a new director disposed of outdated art to make space in the collections. “They’re complex artifacts, and vulnerable in a way that other works of natural history illustration aren’t,” Lescaze said of vintage pieces of paleoart. “Nobody’s going to throw out the John James Audubon, but works of paleoart that are rendered obsolete regularly get discarded. … It’s really important to look back at some of these and say, yeah, they’re not scientifically accurate anymore, but who cares? What else can they teach us?”

Whatever the influences or techniques, paleoart is fundamentally an attempt to glimpse something that can never be fully seen. Anybody who tries to reconstruct prehistory fills in the gaps with their own preoccupations, turning real animals into symbols of obsolescence, savagery, or martial power. Many modern artists are trying to strip these projections out of their art, but changing cultural ideas and paleontological consensus can make doing so difficult. “Evolution is a brush, not a ladder,” the artist Emily Willoughby notes in Dinosaur Art II: not a direct route going anywhere, but, rather, a messy bundle of approaches. It’s only fitting that the art depicting its sweep should be similarly difficult to pin down.