Hong Kong

When associates at Causeway Bay Books in Hong Kong went missing about two years ago—and its scandalous books about mainland Chinese politicians were destroyed not long after—Woo Chih-wai thought he’d lost everything.

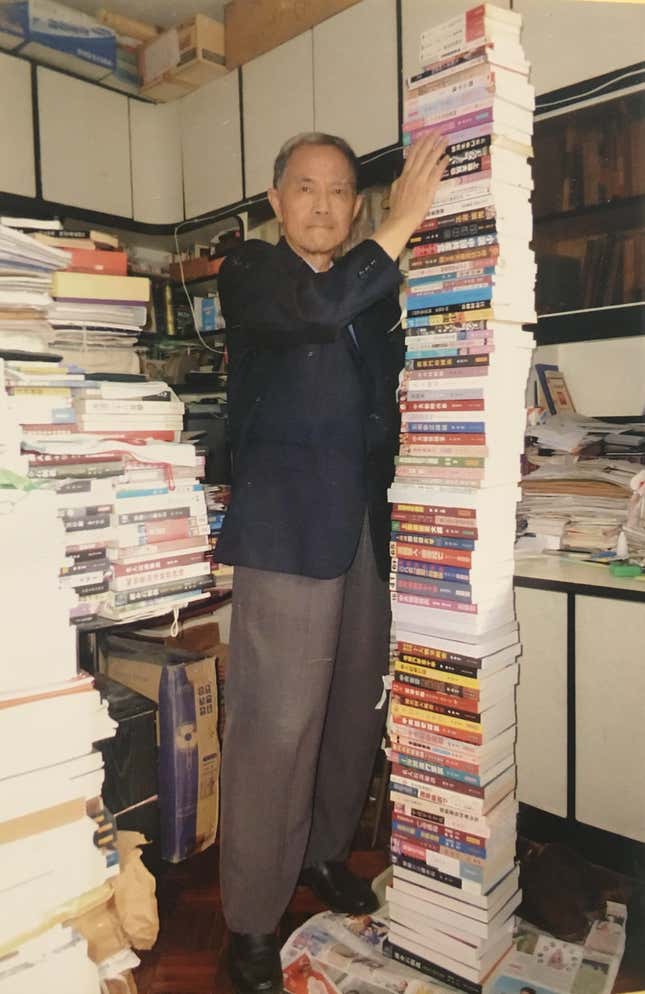

In addition to being the store’s last manager, the 75-year-old was a prolific author, having penned over 120 titles on Chinese politics. The shop’s downfall meant that large stocks—and the main seller—of his books were suddenly gone. The store had specialized in titles banned on the mainland, including salacious titles on the personal lives of Chinese Communist Party leaders. Other publishers, not surprisingly, have proven reluctant to sell Woo’s books, which cover a range of topics from the Cultural Revolution and Tiananmen massacre to the political scandals of the Communist Party and the history of Chiang Kai-shek.

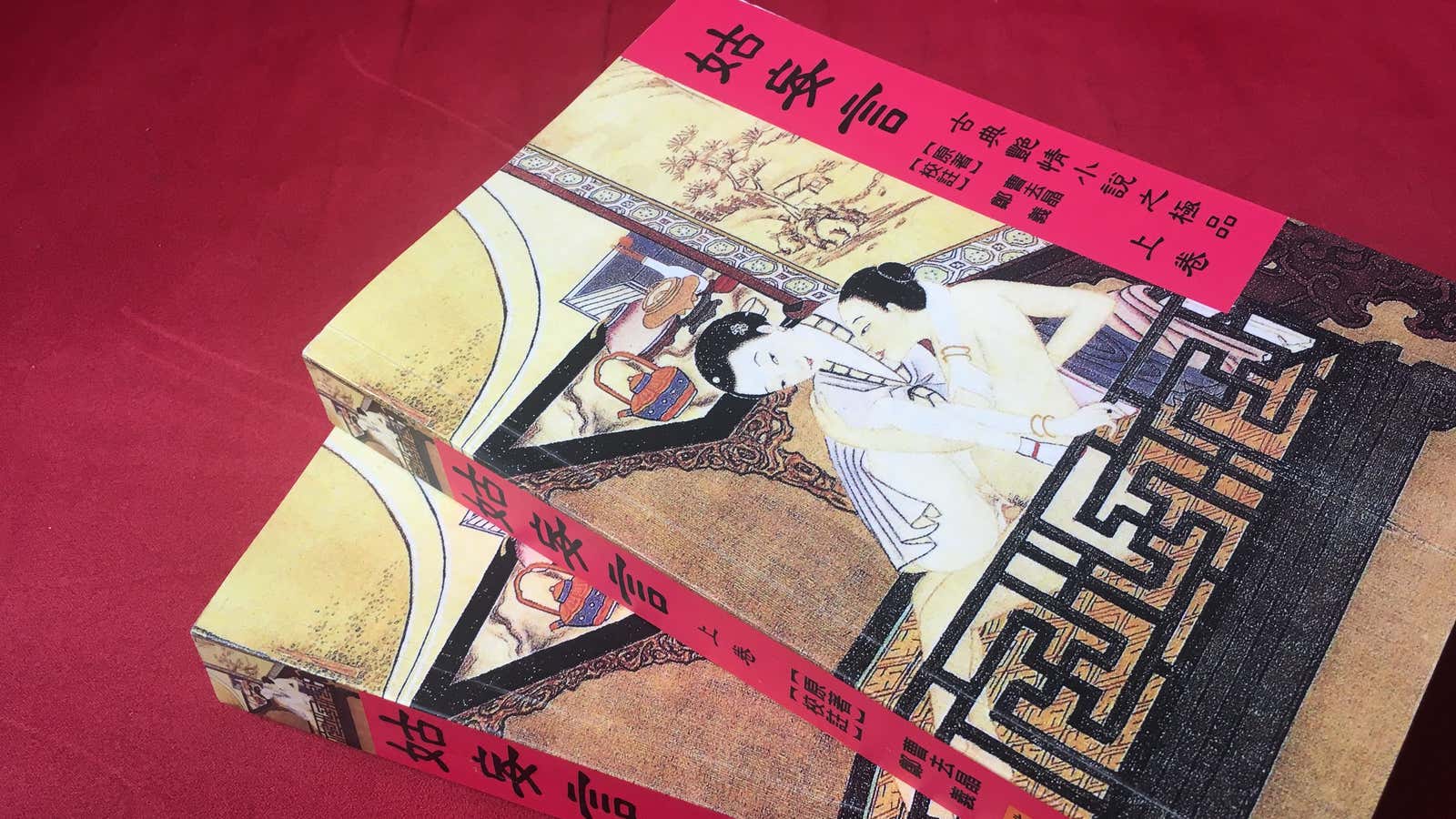

But Woo’s misfortune did prompt him to release a title he never intended to publish. In part an attempt to recuperate his losses, he recently published Preposterous Words, a long-lost erotic classic written in the mid-18th century. Woo’s book offers the full version—never before released, he says—of the original text, together with a preface he wrote (under his pen name Cheng Yi) to introduce and explain the work.

“I’ve been studying this text since 2002,” Woo says. “This is not just an erotic novel full of graphic descriptions of sexual encounters, but a text reflecting the horror of Chinese history that is still relevant today.”

The rediscovery of

Preposterous Words

Preposterous Words was written by Cao Qujing in 1730s during the early period of Qing dynasty. Known as Guwangyan (姑妄言) in Chinese, the title has 1 million characters and is said to be one of the longest novels written during its era. The book was not printed for mass circulation at the time. Only a version of the manuscript was preserved in court at the time, meaning there’d been little trace of it.

Russian sinologist Boris L’vovich Riftin discovered the complete manuscript in 1964, at what is now known as the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg, according to The Cambridge History of Chinese Literature. The manuscript belonged to a collection of some 1,500 books that Russian astronomer K.I. Skachkov took from China in 1863 after a sojourn at the Beijing observatory, says Woo.

Despite Riftin’s discovery, Preposterous Words remained largely unknown, especially compared to the erotic Chinese classics The Plum in the Golden Vase (Jin Ping Mei, 金瓶梅) and The Carnal Prayer Mat (Rouputuan, 肉蒲團). Those works are not only widely circulated, but have also been adapted into TV shows and movies. The erotic comedy Sex and Zen, loosely based on The Carnal Prayer Mat, scored more than HK$18 million (US$2.3 million) in the Hong Kong box office when it was released in 1991. An updated version—3D Sex and Zen: Extreme Ecstasy—became an attraction to Chinese tourists when it was released in Hong Kong in 2011, as the film was banned in mainland China.

Preposterous Words is a fairly recent interest in academia, according to Paola Zamperini, who teaches Chinese literature at Northwestern University in Illinois. “The text was made available to the scholarly community as printed text only in the 1990s,” she says. “It is perhaps the longest novel in late imperial China and also one of the least studied to date.” By contrast, The Plum in the Golden Vase (1617) “was circulated widely in manuscript form at the time of its composition and was already in print by the end of the 17th century.”

Many publishers rejected printing the book because of its sheer volume, according to Woo, and versions published in mainland China and Taiwan decades ago were lacking. A version put out in Taiwan in the mid-1990s was full of mistakes and weighed too much, which did not help sales, says Woo, and a version offered in mainland China in 1999-2000 came from publishers working under the Chinese Communist Party and had 16% of the original text censored out.

Politically incorrect stories

That censored text was related to the political history of China, rather than graphic descriptions of sexual encounters and dirty jokes, Woo discovered upon looking up the original text in the Russian library in 2005. The stories in Preposterous Words are set in the late Ming period of unrest. Some tell of horrendous sexual crimes committed by mobs whose members were originally farmers. “This is seen politically incorrect,” Woo says, noting that the founding of the Chinese Communist Party is based on a farmers’ revolution that liberated the peasants.

Woo copied the original text and brought it back to Hong Kong for further study. As the text is nearly three centuries old, there is no copyright involved, so he decided to publish the title together with the preface he wrote. At first no publishers were willing to sign on, he says, but eventually he found one registered in Vancouver called KF Times Group, along with a printer in Shenzhen. This summer they churned out 220 copies, which he brought back to Hong Kong. “The printer in Shenzhen was too afraid of getting caught, as the content is sensitive,” he says. “It had to be done quietly.”

The final product is a book in two volumes, totaling nearly a thousand pages and selling for about US$150.

The Chinese title of Preposterous Words literally means “talk for talk’s sake.” The stories are set during the Wanli reign (1573-1628), which was the turning point for the decline of Ming dynasty. The plot revolves around five major characters who were historical figures in their past lives. They were penalized by the King of Ghosts to serve sentence for the political crimes they previously committed by reincarnating into turbulent lives that make them suffer. The text contains graphic and jaw-dropping descriptions of extreme sexual activities.

The depiction of sex in Preposterous Words is much more transgressive than in works such as The Plum in the Golden Vase, says Zamperini. “[It] includes bestiality and what we would call today S&M.”

The repressed attitude toward sex among many Chinese today is a relatively modern phenomenon. Paul Rakita Goldin wrote in his book The Culture of Sex in Ancient China that scholars and writers “discussed sex openly and seriously” in ancient times.

Hong Kong author Tommy Sham says text depicting sex can be traced to the Tang dynasty (618-907). “Chinese people were not shy to talk about sex at all in ancient times,” he says. “It was politics and the rulers’ ambition to control that suppressed people’s desire for sex.”

The wild sex depicted in such novels also served another function. “Sex is deployed to show the level of corruption and decadence of the male characters, and this is the case in Preposterous Words, in The Plum in the Golden Vase, and other works composed in the Ming and the Qing dynasty,” says Zamperini.

Woo says he sold most copies of his version of Preposterous Words through his own network. He’s now working on printing a new edition in a month or two that he hopes will be distributed in the United States.