The Surprising Revolt at the Most Liberal College in the Country

Activists are disrupting lectures to protest "white supremacy," but many students are taking steps to stop them.

At Reed College, a small liberal-arts school in Portland, Oregon, a 39-year-old Saturday Night Live skit recently caused an uproar over cultural appropriation. In the classic Steve Martin skit, he performs a goofy song, “King Tut,” meant to satirize a Tutankhamun exhibit touring the U.S. and to criticize the commercialization of Egyptian culture. You could say that his critique is weak; that his humor is lame; that his dance moves are unintentionally offensive or downright racist. All of that, and more, was debated in a humanities course at Reed.

But many students found the video so egregious that they opposed its very presence in class. “That’s like somebody … making a song just littered with the n-word everywhere,” a member of Reedies Against Racism (RAR) told the student newspaper when asked about Martin’s performance. She told me more: The Egyptian garb of the backup dancers and singers—many of whom are African American—“is racist as well. The gold face of the saxophone dancer leaving its tomb is an exhibition of blackface.”

Such outrage has been increasingly common in the course, Humanities 110, over the past 13 months. On September 26, 2016, the newly formed RAR organized a boycott of all classes in response to a Facebook post from the actor Isaiah Washington, who urged “every single African American in the United States that was really fed up with being angry, sad and disgusted” over police shootings to stay home on Monday. Of the 25 demands issued by RAR that day, the largest section was devoted to reforming Humanities 110.

A required year-long course for freshmen, Hum 110 consists of lectures that everyone attends and small break-out classes “where students learn how to discuss, debate, and defend their readings.” It’s the heart of the academic experience at Reed, which ranks second for future Ph.D.s in the humanities and fourth in all subjects. (Reed famously shuns the U.S. News & World Report, as explained in a 2005 Atlantic article by a former Reed president.) As Professor Peter Steinberger details in a 2011 piece for Reed magazine, “What Hum 110 Is All About,” the course is intended to train students whose “primary goal” is “to engage in original, open-ended, critical inquiry.”

But for RAR, Hum 110 is all about oppression. “We believe that the first lesson that freshmen should learn about Hum 110 is that it perpetuates white supremacy—by centering ‘whiteness’ as the only required class at Reed,” according to a RAR statement delivered to all new freshmen. The texts that make up the Hum 110 syllabus—from the ancient Mediterranean, Mesopotamia, Persia, and Egypt regions—are “Eurocentric,” “Caucasoid,” and thus “oppressive,” RAR leaders have stated. Hum 110 “feels like a cruel test for students of color,” one leader remarked on public radio. “It traumatized my peers.”

RAR was created on boycott day to mourn the deaths of black Americans at the hands of police nationwide. Speeches and open mics highlighted the angst that many students feel on a campus where African Americans account for just 5 percent of those enrolled. What’s more, the graduation rate among black students at the time was 65 percent, compared with 79 percent for all students. RAR has a sympathetic audience: Reed is home to the most liberal student body of any college, according to The Princeton Review. It’s also ranked the second most-studious—a rigor inculcated in Hum 110.

A major crisis for Reed College started when RAR put those core qualities—social justice and academic study—on a collision course.

Beginning on boycott day, RAR protested every single Hum lecture that school year. In-class protests are very rare on college campuses. During the nationwide upsurge of student activism tracing back to 2015, protesters have occupied administrative buildings, stormed into libraries, shut down visiting speakers in auditoriums, and walked out of classrooms—but they hardly ever disrupt the classroom itself. RAR has done so more than 60 times.

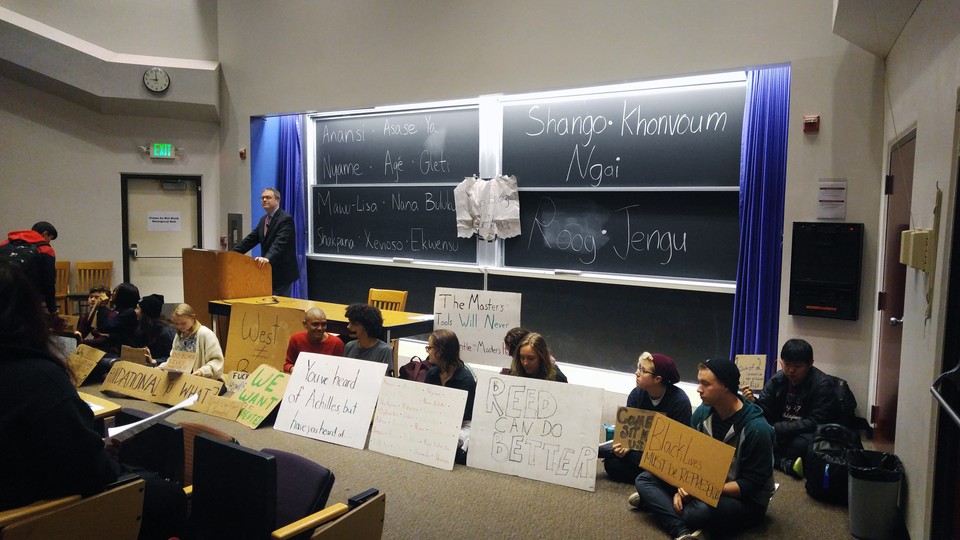

A Hum protest is visually striking: Up to several dozen RAR supporters position themselves alongside the professor and quietly hold signs reading “We demand space for students of color,” “We cannot be erased,” “Fuck Hum 110,” “Stop silencing black and brown voices; the rest of society is already standing on their necks,” and so on. The signs are often accompanied by photos of black Americans killed by police.

One of the first Hum professors to request that RAR not occupy the classroom was Lucía Martínez Valdivia, who said her preexisting PTSD would make it difficult to face protesters. In an open letter, RAR offered sympathy to Martínez Valdivia but then accused her of being anti-black, discriminating against those with disabilities, and engaging in gaslighting—without specifying those charges. When someone asked for specifics, a RAR leader replied, “Asking for people to display their trauma so that you feel sufficiently satisfied is a form of violence.”

But another RAR member did offer a specific via Facebook: “The appropriation of AAVE [African American Vernacular English] on her shirt during lecture: ‘Poetry is lit’ is a form of anti-blackness.”

During Martínez Valdivia’s lecture on Sappho, protesters sat together in the seats wearing all black; they confronted her after class, with at least one of them yelling at the professor about her past trauma, bringing her to tears. “I am intimidated by these students,” Martínez Valdivia later wrote, noting she is “scared to teach courses on race, gender, or sexuality, or even texts that bring these issues up in any way—and I am a gay mixed-race woman.” Such fear, she revealed in an op-ed for The Washington Post, prompted some of her colleagues— “including people of color, immigrants, and those without tenure”—to avoid lecturing altogether.

National coverage of the Hum 110 crisis has focused primarily on the clashes between RAR and faculty, but what about the majority of students not in RAR? I spoke with a few dozen of them to get an understanding of what campus was like last year, and a clear pattern emerged: intimidation, stigma, and silence when it came to discussing Hum 110, or racial politics in general.

The most popular public forum at Reed is Facebook, where social tribes coalesce and where the most emotive and partisan views get the most attention. “Facebook conversations at Reed bring out the extreme aspects of political discourse on campus,” said Yuta, a sophomore who recently co-founded a student group, The Thinkery, “dedicated to critical and open discussion.”(The Atlantic used only first names for students out of concern for online harassment.) Raphael, the founder of the Political Dissidents Club, warned incoming students over Facebook that “Reed’s culture can be stifling/suffocating and narrow minded.”

It can also be bullying. When the parent of a freshman rebuked RAR for derailing a lecture, a RAR supporter tagged the parent’s employer in a post. In mid-April, when students were studying for finals, a RAR leader grew frustrated that more supporters weren’t showing up to protest Hum 110. In a post viewable only to Reed students, the leader let loose:

To all the white & able(mentally/physically) who don’t come to sit-ins(ever, anymore, rarely): all i got is shade for you. [... If] you ain’t with me, then I will accept that you are against me. There’s 6 hums left, I best be seein all u phony ass white allies show-up. […] How you gonna be makin all ur white supremacy messes & not help clean-up your own community by coming and sitting for a frickin hour & still claim that you ain’t a laughin at a lynchin kinda white.

The RAR leader proceeded to call out at least 15 students by name. One, named Patrick, defended himself, saying in part, “I didn’t realize this was [your] opinion of me as a friend … I will not give you my support simply because you are leading a noble cause.” The leader referred to that defense as “white supremacy.” Another leader used a vulgar insult, followed by “White tears white tears.”

Nonwhite students weren’t spared; a group of them agreed to “like” Patrick’s comment in a show of support. A RAR member demanded those “non-black pocs [people of color]” explain themselves, calling them “anti-black pos [pieces of shit].” Another member tried to get Patrick on track: “Hey man, everyone getting called out on here, me included, is getting a second chance tomorrow to wake up and make the right decision.”

As tensions continued to mount, one student decided to create an online forum to debate Hum 110. Laura, a U.S. Army veteran who served twice in Afghanistan, named the Facebook page “Reed Discusses Hum 110.” But it seemed like people didn’t want to engage publicly: “I did receive private responses from people who wanted to participate but who were afraid to do so,” she said. One student drafted a comment but deleted it “because I realized it wasn’t worth the risk of having basically 80 percent of my social circle vilify me for my opinion on an honestly relatively minor issue.”

Another student wrote to Laura in a private message, “I'm coming into this as a ‘POC’ but I disagree with everything [RAR has been] saying for a long time [and] it feels as if it isn't safe for anyone to express anything that goes against what they're saying.” Laura could relate—her father “immigrated from Syria and was brown”—so she stood in front of Hum 110 just before class to distribute an anonymous survey to gauge opinions about the protests, an implicit rebuke to RAR. Laura, who lives in the neighboring city of Beaverton, said she saw this move as risky. “I would’ve rethought what I did had I lived on campus,” she said.

If Facebook is no place to debate Hum 110, what about the printed page? Not so much: During the entire 2016–17 school year, not a single op-ed or even a quote critical of RAR’s methods—let alone goals—was published in the student newspaper, according to a review of archived issues. The only thing that comes close? A clarification regarding a school dance:

[RAR] requested that students, specifically white students, give a suggested amount of five dollars to RAR if they planned on consuming black and brown culture at the ball. This money, explicitly regarded as reparations, was collected at the door by student activists ... [the ball organizer responded], “we are in support of Reedies Against Racism but want to make it clear that their event is unaffiliated with ours.”

The student magazine, The Grail, did publish a fair amount of dissent over RAR—but almost all anonymously. The sole exception was Ema, who contrasted the dangers of growing up in Mexico City with the “coddling” culture promoted by RAR. In “Unpopular Opinion,” an anonymous student—“a low-income, first-generation American person of color”—recognizes RAR’s “valid points,” but said that its supporters’ “holding pictures of dead children in my face” during Hum 110 is “making it harder for me to learn.”

This school year, students are ditching anonymity and standing up to RAR in public—and almost all of them are freshmen of color. The turning point was the derailment of the Hum lecture on August 28, the first day of classes. As the Humanities 110 program chair, Elizabeth Drumm, introduced a panel presentation, three RAR leaders took to the stage and ignored her objections. Drumm canceled the lecture—a first since the boycott. Using a panelist’s microphone, a leader told the freshmen, “[Our] work is just as important as the work of the faculty, so we were going to introduce ourselves as well.”

The pushback from freshmen first came over Facebook. “To interrupt a lecture in a classroom setting is in serious violation of academic freedom and is just unthoughtful and wrong,” wrote a student from China named Sicheng, who distributed a letter of dissent against RAR. Another student, Isabel, ridiculed the group for its “unsolicited emotional theater.”

Two days later, a video circulated showing freshmen in the lecture hall admonishing protesters. When a few professors get into a heated exchange with RAR leaders, an African American freshman in the front row stands up and raises his arms: “This is a classroom! This is not the place! Right now we are trying to learn! We’re the freshman students!” The room erupts with applause.

I caught up with that student, whose name is Pax. “This is a weird year to be a freshman,” he sighed. Pax is very mild-mannered, so I asked what made him snap into action that morning. “It felt like both sides [RAR and faculty] weren’t paying attention to the freshman class, as it being our class,” he replied. “They started yelling over the freshmen. It was very much like we weren’t people to them—that we were just a body to use.”

Next I met the student who shot the video. A sophomore from India, he serves as a mentor for international students. (He asked not to be identified by name.) “A lot of them told me how disappointed they were—that they traveled such a long distance to come to this school, and worked so hard to get to this school, and their first lecture was canceled,” he said. He also recalled the mood last year for many students of color like himself: “There was very much a standard opinion you had to have [about RAR], otherwise people would look at you funny, and some people would say stuff to you—a lot of people were called ‘race traitors.’”

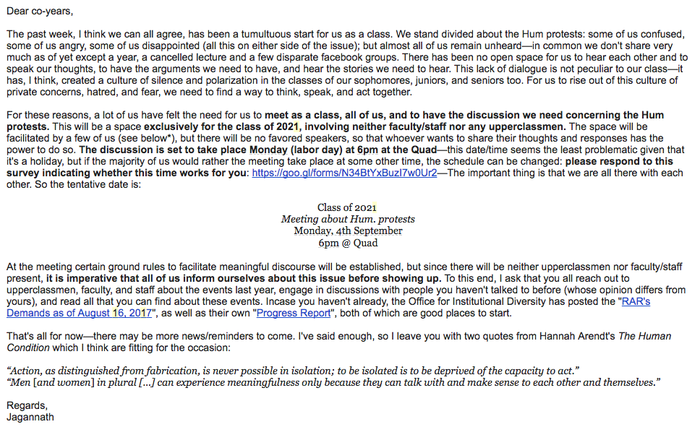

Another student from India, Jagannath, responded to the canceled lecture by organizing a freshmen-only meeting on the quad. “For us to rise out of this culture of private concerns, hatred, and fear, we need to find a way to think, speak, and act together,” he wrote in a mass email. Jagannath told me that upperclassmen warned him he was “very crazy” to hold a public meeting, but it was a huge success; about 150 freshmen showed up, and by all accounts, their debate over Hum 110 was civil and constructive. In the absence of Facebook and protest signs, the freshmen were taking back their class.

For the anniversary of the boycott that gave rise to RAR, the group planned another boycott, on September 25. In the intervening year, the Reed administration had met many of RAR’s demands, including new hires in the Office of Inclusive Community, fast-tracking the reevaluation of the Hum 110 syllabus that traditionally happens every 10 years, and arranging a long series of “6 by 6 meetings”—six RAR students and six Hum professors—to solicit ideas for that syllabus. (Those meetings ended when RAR members stopped coming; they complained of being “forced to sit in hours of fruitless meetings listening to full-grown adults cry about Aristotle.”)

“The movement cannot continue to manufacture an enemy that has agreed to review the syllabus [and] bended over backwards on all accounts to accommodate the free speech of the protesters,” wrote Misha, another freshman, in the first op-ed critical of RAR published in the school paper. Yet the more accommodation that’s been made, the more disruptive the protests have become—and the more heightened the rhetoric. “Black lives matter” was the common chant at last year’s boycott. This year’s? “No cops, no KKK, no racist U.S.A.” RAR increasingly claims those cops will be unleashed on them—or, in their words, Hum professors are “entertaining threatening violence on our bodies.”

For the anniversary, RAR arranged an open mic for students of color. Rollo, a freshman from Houston, described how difficult it was to grow up poor, black, and gay in Texas. He then turned to RAR: “No, I won’t subject myself to your politically correct ideas. No, I won’t allow myself to be a part of your cause.” He criticized the “demagoguery” that “prevents any comprehensive conversation about race outside of ‘racism is bad.’”

Rollo later told me that RAR “had a beautiful opportunity to address police violence” but squandered it with extreme rhetoric. “Identity politics is divisive,” he insisted. As far as Hum 110, “I like to do my own interpreting,” and he resents RAR “playing the race card on ancient Egyptian culture.”

Over at the lecture hall, RAR covered the door with photos of police victims so that anyone entering would have to rip them. Shortly into Ann Delehanty’s lecture on The Iliad, a RAR “noise parade” shut it down—the third class canceled that month, after Kambiz GhaneaBassiri refused to teach the Epic of Gilgamesh in front of signs tying him to white supremacy. Where Delehanty had just stood, a RAR leader read a statement about how Reed is complicit in “modern-day slavery” because its operating bank, Wells Fargo, has ties to private prisons.

But her words faltered as she watched the freshmen walk out. “The thing that heartens me,” said Pax, “is that most of the student body followed the professor into another classroom, where she continued the lecture.”

Support for RAR seems to be collapsing; only about 100 students were involved in this year’s boycott, a quarter of last year’s crowd. There haven't been any Hum protests since the upperclassmen who participated in the noise parade were barred from lectures. RAR’s list of demands keeps growing, but its energy is now focused on Wells Fargo. That could change when reforms to the Hum syllabus are announced this fall, but for now, the lecture hall is free of protesters.

Reed is just one college—and a small one at that. But the freshman revolt against RAR could be a blueprint for other campuses. If the “most liberal student body” in the country can reject divisive racial rhetoric and come together to debate a diversity of views, others could follow.