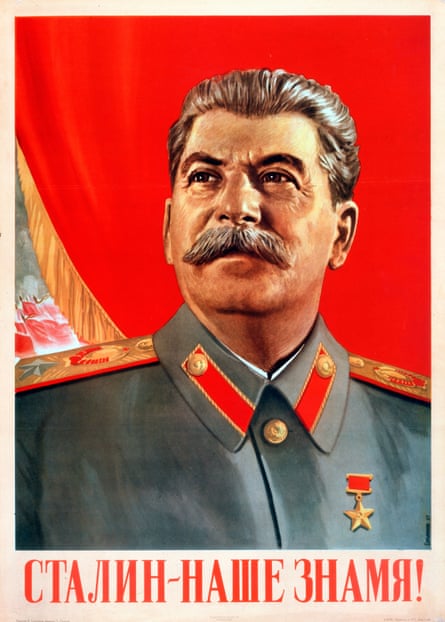

My first memory of the outside world was watching my parents as they heard an announcement on the radio that Joseph Stalin was dead. The news was greeted not with relish but with awe and apprehension. The Soviet dictator was a colossal figure in the mid-20th century, even in the west. His death on 5 March 1953 was a reference point not just for the Soviet people but for the wider world. Now it is history.

That is until now. With The Death of Stalin, director Armando Iannucci has brought the story surrounding the dictator’s last hours and the political scramble among his potential successors to a modern audience. The subject is a strange choice. Where the suicide of Hitler in the bunker has a squalid drama, captured effectively in the 2004 film Downfall, the death of Stalin has to have the drama squeezed out of it, drop by drop. He did not take his own life nor, as far as the evidence suggests, did anyone else. He died of natural causes at his dacha outside Moscow, surrounded by his fearful and sycophantic court.

These courtiers had dithered about whether to call a doctor to tend their dying leader, not least because with his death, new job opportunities beckoned. In the months that followed, his former colleagues jostled, but the outcome was a sharing of power. None of them was the new Stalin. The one man who thought he might be – Stalin’s fellow Georgian and odious former head of the secret police, Lavrentiy Beria – was loathed by the others. He was arrested three months after Stalin’s death and, in circumstances still not entirely clear, executed in December.

All of this is recreated in parody. The film itself is littered with historical errors, the result of trying to make a black comedy out of rather unpromising material. Some of the errors matter. Vyacheslav Molotov was not foreign minister when Stalin died but had been sacked in 1949, though he became so again in the post-Stalin reshuffle. Marshal Zhukov (not Field Marshal) was a local field commander when Stalin died, exiled to the provinces to satisfy Stalin’s paranoid jealousy at his highly successful wartime deputy supreme commander. He became deputy minister of defence in the post-Stalin government but he was not the commander of the Red Army in March 1953. Nikita Khrushchev chaired the meeting to reorganise the government, not Georgy Malenkov, giving him a status he does not enjoy in the film. Beria was arrested three months after Stalin died, not almost simultaneously, and he was not head of the security forces, a job he had given up in 1946.

This might be viewed as cinematic licence. The real history has its moments, but it is certainly duller and more drawn-out, while the film moves on at a breathless pace, hamming up the story for laughs. But is the death of Stalin, and the murderous regime he ran, really something to ham up? The audience reaction to Downfall was serious reflection about the Hitler dictatorship and its grotesque finale. The Death of Stalin suggests that in the end Soviet politics under Stalin can be treated as opera buffa.

This contrast is not perhaps accidental. There still remains a certain ambivalence in the public memory of Stalin. Almost everything is now known about the systematic and large-scale abuse of human rights that occurred under Stalin’s rule – a scale that challenges belief. Yet Stalin is remembered as the man who modernised the Soviet Union and defeated the German attempt to conquer it, if not quite arm-in-arm with Britain and the US, then at least in expedient collaboration. He was lauded at the time in a western world that knew little about the horrors of the regime. For better or worse, the conventional narrative of the second world war in the west still has Stalin on the side of the angels, and Hitler in league with the devil.

For the Soviet people, the death of Stalin was a disguised blessing. Although millions mourned him with a genuine outpouring of grief, his death abruptly interrupted a renewed wave of terror against any potential rivals, against ideological backsliders, and above all against the Soviet Jews who had survived the Holocaust. The final years of alleged plots, denunciations, and summary deaths and assassinations, threatened to recreate the years of the Great Terror of 1937-8, in which more than 600,000 people perished at the hands of the state, with Stalin’s approval.

The film touches on the last of these regime fantasies, the notorious Doctors’ Plot, directed principally, though not exclusively, at Jewish doctors. In January 1953, the plot was announced to the Soviet public. Senior medical experts were arrested and tortured into making bizarre confessions as members of an alleged “Zionist terrorist gang”.

Stalin’s personal physician, Vladimir Vinogradov, was put in shackles on Stalin’s orders after the dictator allegedly found in the doctor’s notes a recommendation that his patient should give up work. It has never been entirely clear if Stalin himself believed the plot really existed, but it never mattered. His brutal authority was maintained on the Hobbesian principle that no one was secure in the Soviet state. “I trust no one,” he is supposed to have said, “not even myself.” One consequence of this final spasm of violence was the difficulty in finding a doctor who could treat the dictator in his dying hours.

The last months of savage and arbitrary repression are presented more or less in caricature, almost at times as farce. The underlying truth is, of course, there. Stalin’s last years were an awful waiting time for his party entourage and for the millions who fell victim to the caprices of their bizarre leader. But it must surely be the case that those victims – murdered or incarcerated on trumped-up charges forced out of them by torturers, or rounded up and sent to the gulag to give the fantasies of conspiracy or bourgeois contamination some apparent plausibility – deserve a film that treats their history with greater discretion and historical understanding.

This is not a film likely to be viewed with enthusiasm in the current Kremlin. Historical distortion or defamation is covered by legislation. The presentation of Stalin and his cronies as a collection of foul-mouthed misfits serves little useful purpose. It will certainly not help to understand the Russia of the 1950s while it mocks by implication the Russia of today, a country still shaped in some ways by the legacy of Stalin’s modernisation drives and the operation of the Stalinist state. His death allowed Khrushchev, three years later, to denounce the excesses of the dictator’s last years but it took a long time to dismantle the structures of repression. The historical shadow of the dictator lay for years over the Soviet system and has not entirely disappeared.

In the Lenin Museum outside Moscow, the authorities have recreated the room where the central committee met. At the head of the table is the chair used by Stalin. When I visited, we were invited to sit in the chair, but we shifted about uneasily and in the end no one did. Easy to believe that the ghost of the long-dead dictator still haunts the room. If he is now viewed widely as one of history’s monsters, his was an extraordinary and riveting power. A film that portrays the way that power worked would challenge any director, but it is not a challenge that The Death of Stalin has met. It is entertainment, but poor history.

- The Death of Stalin is out in the UK on 20 October

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion