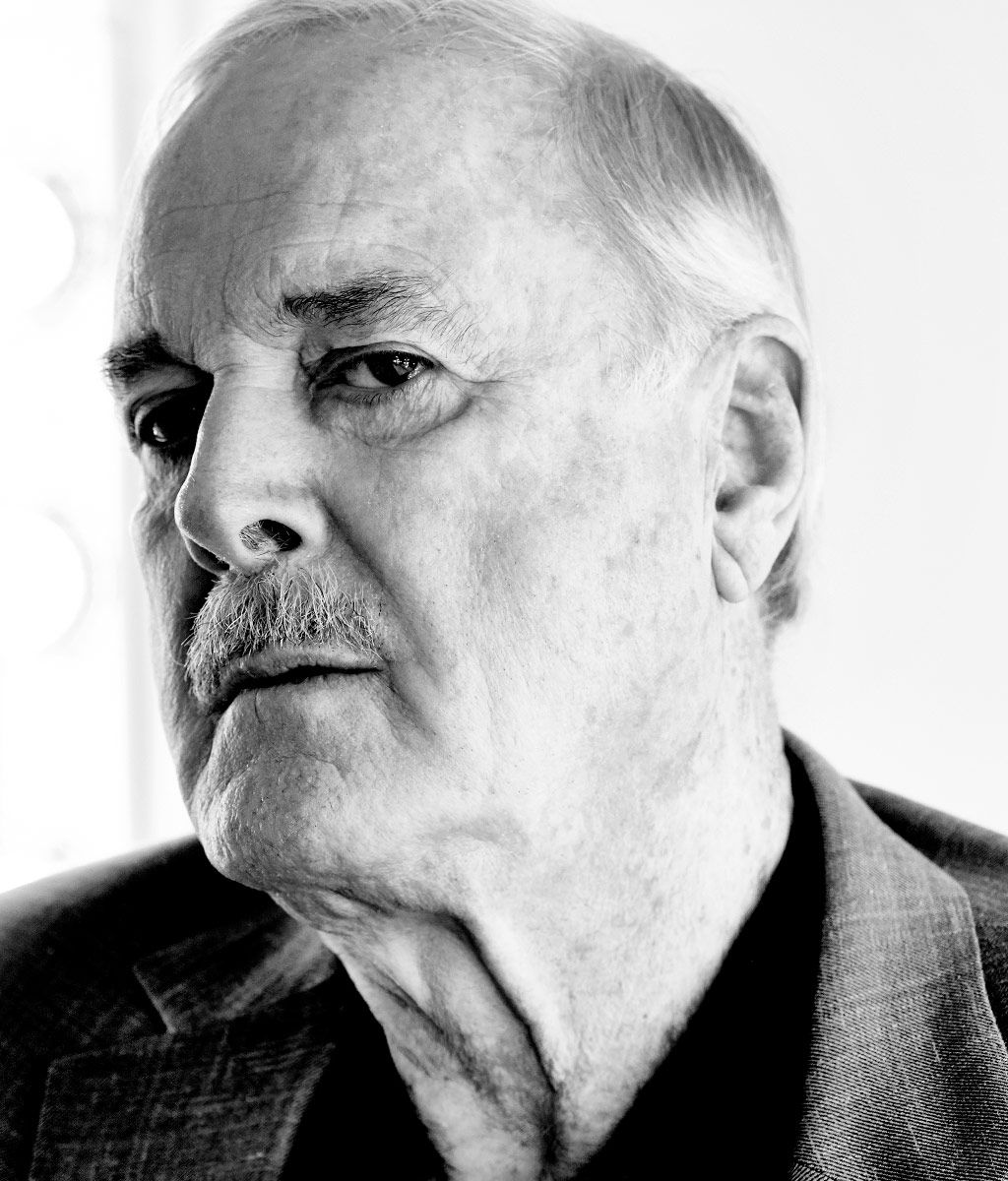

“I want to murder this thing,” says John Cleese, fiddling with a medical contraption that’s attached to his leg. The 77-year-old founding member of the Monty Python comedy troupe — arguably humanity’s greatest comedic endeavor — and the star and co-creator of perennial best-sitcom-ever contender Fawlty Towers, is in his office on a cool London summer morning, going about things with what I suspect is his usual air of amused irritation. “I’ve got a leg infection and now have a fucking cube” — Cleese, sitting in a brown leather chair, pulls up a leg of his jeans and taps on a pump with his index finger — “sucking out the scunge. It’s quite annoying.”

So, it seems, are a great many things for the charmingly cantankerous Cleese, who still performs regularly, both onscreen and onstage, the latter typically as a one-man show. “We’re living in the age of assholes now. It’s breathtaking,” he says, eyes wide with wonder. “They’re running everything.” His leg beeps. “The cube does that when it’s been unplugged,” Cleese explains, before disconnecting the device entirely. “That’s much better,” he says, stretching out. “Now let’s talk.”

I have a bit of a morbid question.

Please.

You’re 77 years old.

I am.

You have a scunge pump attached to your leg.

I do.

Is death funny?

It is. Death is certainly present in my life, and there’s humor to be mined from it. Somebody was saying to me last week that you can’t talk about death these days without people thinking you’ve done something absolutely antisocial. But death is part of the deal. Imagine if, before you came to exist on Earth, God said, “You can choose to stay up here with me, watching reruns and eating ice cream, or you can be born. But if you pick being born, at the end of your life you have to die — that’s nonnegotiable. So which do you pick?” I think most people would say, “I’ll give living a whirl.” It’s sad, but the whirl includes dying. That’s something I accept.

So has what you find funny changed as you’ve gotten older?

Well, I could easily rattle off a rote answer for you.

Would you mind not?

Okay, let me really try and think about my answer. I do think my sense of humor has expanded but that’s to do both with age and with being in therapy. I’ll give you an example of what I mean: In the ’70s, I went to see a play by a man named Alan Ayckbourn. He’s not very well known in America and I think that’s because his humor is all about rather ineffectual men, and in America when men go wrong they become psychos, whereas in England they become wimps. So Americans don’t respond to his work. Anyway, in addition to comedy, Ayckbourn used serious emotions in his work, and the first time I ever saw that, I was uncomfortable because I would be feeling sad for one of his characters and then suddenly something funny would happen and I found the emotional back-and-forth confusing. I don’t have that problem anymore. I used to think of comedy as its own separate bracket, and the less attractive parts of life were to be kept away from it because they stopped the comedy from being bright. Over time, therapy expanded my comfort level with emotional areas that otherwise would’ve made me uncomfortable — things like death, for instance. So I’m less hesitant about more material, if that makes sense. But that’s about me specifically. I don’t have an answer for what has changed generally about what the culture finds funny.

Why is that? Are you just disinterested?

I don’t know much about contemporary comedy. I don’t watch any. I’m 77. I will almost certainly be dead within 10 years — maybe I’ll get 15. So to sit down to watch a sitcom seems to be a rather futile way of passing the time. It’s as simple as that. If I have a free evening, I’ll read, because there are so many things I don’t begin to understand and that I’d like to try and get a handle on before I’m dead. I’d rather do that than watch comedy.

Given your own disinterest in watching comedy, is it at all weird to you that people still want to talk about Monty Python?

The more interesting thing to me is seeing how different types of people respond to Monty Python. People always say the English have a different sense of humor than Americans, but I think America itself has two senses of humor. There are the folk in the Midwest and in the South who are much more literal-minded in what they laugh about, and then once you go to the coasts you get an audience that’s totally at home with irony and absurdity.

What accounts for that difference?

To be perfectly honest, the people on the coasts and in the big cities are a lot smarter. Whenever you’re out in the sticks with a slower audience, it’s not that they enjoy the comedy less, because they’re still laughing, it’s that they don’t enjoy it as quickly. It’s always a bit disconcerting when people are laughing three seconds into the next joke because they just got the last one.

When’s the last time someone who you thought was stupid made you laugh?

That would be the film director I worked with two days ago.

What happened?

Just things he wanted to cover with the camera. It was a complete waste of time.

I’m glad you were able to find the humor there.

There’s wonderful humor everywhere. I’ll give you an example: I was in Miami, only about four or five months ago, and I had a massage in the hotel spa. Afterward they called me: “Mr. Cleese, you left your shoes in the spa. Can we send them up to your room?” I said, “Oh, how nice of you.” So, five minutes later, knock knock, someone opens the door. “Mr. Cleese, here’s your shoes.” “Thank you.” “Could I see some form of identification?” “Now, you know I’m Mr. Cleese because you just called me Mr. Cleese, and you know the room that Mr. Cleese was in because you came to my room number. So what are we doing asking for identification?” And the guy said, “Well, I’m sorry, I still need to see some form of identification.” So I went over and I got a copy of my autobiography and I said, “That’s me there on the cover. And down there it says ‘John Cleese.’” You know what he said to me? He said, “I’m sorry, that’s not good enough.” You couldn’t write something as wonderful as that.

Does comedy have any surprises for you anymore?

Not many. Jesus is said to have never laughed in the Bible, and I think it’s because laughter contains an element of surprise — something about the human condition that you haven’t spotted yet — and Jesus was rarely surprised. I still laugh, but many of the things that would have made me laugh 30 years ago — paradoxes about human nature — wouldn’t make me laugh anymore because I just believe them to be true. They’re not revelations.

Just to go back to subject of American audiences: You’re lecturing at Cornell in September. Have you been following any of the controversies over free speech on college campuses? You’ve talked often in public about your frustration with the idea that political correctness has run amok.

I haven’t spoken at Cornell for eight years, so I can’t say I have firsthand experience of how receptive students are to having their thinking challenged. I’d planned to go back to the school sooner but I was hit with a divorce and didn’t have time to return because I was busy doing money-grubbing work to help pay for the settlement. So I’m quite curious to see how things are now. In fact, other comedians have tried to warn me off of speaking at colleges — they tell me it’s not worth the trouble. Jon Stewart said something like that to me about two years ago. But the thing about political correctness is that it starts as a good idea and then gets taken ad absurdum. And one of the reasons it gets taken ad absurdum is that a lot of the politically correct people have no sense of humor.

Because they’re scolds?

Because they have no sense of proportion, and a sense of humor is actually a sense of proportion. It’s the sense of knowing what’s important. In my stage show I tell jokes that make the audience roar with laughter, jokes about the Australians or the French or the Canadians or the Germans or the Italians. I make all these jokes and everybody laughs — and we don’t hate those groups of people, do we? Take this joke: “A guy walks into a bar and says to the barman, ‘You hear the latest Irish joke?’ The barman says, ‘I should warn you, I’m Irish.’ So the guy says, ‘All right then, I’ll tell it slowly.’” That’s funny! But if you tell that joke and replace “Irish” with “barman who isn’t very intelligent” it isn’t funny at all. Why should we sacrifice laughter to the cause of politically correctness if that laughter isn’t rooted in nastiness? This actually reminds me of an idea I had: Every year at the U.N. they should vote one particular nation to be the butt of the joke.

“This year, all cultural jokes will henceforth be made at the expense of the Danes.”

That’s right. They would just have to accept that they’re the butt of the joke for a year. People find it hard to believe this, but unless we’re talking about puns and wordplay, all humor is essentially critical. So to eliminate jokes that are at the expense of other people is to eliminate most jokes. If you laugh at someone, it’s because his behavior is inappropriate. That’s why you can’t really be funny about Jesus Christ or St. Francis of Assisi, because everything they do is pretty appropriate.

Didn’t Monty Python make a whole movie satirizing Jesus?

Not Jesus, his followers. That’s the key difference.

I get what you’re saying here but if a certain group of people says particular jokes are offensive to them, do you really want to be in favor of reinforcing power dynamics that those people find hurtful? I can’t help but think that when certain people today are saying everyone else is too sensitive — and maybe this is a straw-man example — but it’s akin to certain people 80 years ago saying, “Blackface comedy is just affectionate teasing. What’s the big deal?” There are reasons certain forms of entertainment get challenged.

It’s not that simple. At what point are we allowed to make a joke? After the Charge of the Light Brigade, say, how many years had to pass for it to be acceptable to make jokes about the dead British?

Seven years.

Of course, seven years. How foolish of me. In A Fish Called Wanda my character says to Kevin Kline’s character that the North Vietnamese won the Vietnam War. Kevin’s character then says that the Americans didn’t lose that war — it was a tie. So clearly, enough time had passed to allow for us to make jokes about the Vietnam War. And similarly, if I can make jokes about Americans or English or Germans but I can’t make jokes about black people, then the question is this: When will we be able to treat black people in the same way that we treat Germans?

When they’re treated equally outside of comedy. I don’t think anyone would seriously argue that Germans are dealing with systematic oppression.

Well that’s right, but when will be able to say things are equal? Where’s the line? Here’s another example: Americans love jokes about English dentistry. Now that’s not very nice, is it? Have you ever heard an Englishman saying, “Stop persecuting me?” So where’s the line about what’s allowable? It’s very thin, wherever it is.

I think the line is actually pretty thick: The people who historically have had more power in a society don’t get to decide what’s offensive to those who historically have had less power. Eighty percent of people out there on the sidewalk will tell you they are oppressed by the system. All I’m saying is that all these definitions and rules are not cut-and-dried. Let me tell you something my wife told me which I thought was very funny: It’s the difference between a black fairy tale and a white fairy tale. You know this one?

No, I don’t.

The white fairy tale starts, “Once upon a time”; and the black fairy tale starts, “You motherfuckers ain’t gonna believe this shit.” Is that in any way unpleasant about black people? What they’ve said in the latter joke is much more fun and humorous than white people’s “once upon a time.” The problem is that people are knee-jerk in thinking something is offensive. Sometimes in my show I say, “There were these two Mexicans” and immediately the whole audience goes, “Oooh.” People think something is going to be offensive before it’s even been said. The story I then tell involves an American patrol boat in the Gulf of Mexico. The guy on the boat is cruising along, and suddenly sees two Mexicans going for the border. The guy says, “Hey, what are you doing?” And the Mexicans say, “We’re invading America.” And the guy on the boat says, “What, just the two of you?” And the Mexicans say back, “Oh no, we’re the last ones. The others are already there.”

Oy, John.

But is that a nasty joke? Think about the content of it. The Mexicans are actually the heroes! They’ve won! There are millions of Mexicans in America. Are we trying to pretend that isn’t the case? So is that a nasty story to tell? I don’t think it is. And isn’t it condescending to say that certain people can’t take a joke? But when there is a nasty quality to the joke, then that’s not good humor. That’s cruel, and that’s something we need to avoid.

Let’s shift gears a little. You’ve lived in America part-time for decades. Did Donald Trump’s election change your thinking about Americans?

Mm-hmm. What I found surprising was that the least successful people supported Trump. You understand the wealthy wanting tax cuts, but why on Earth did the less successful people think Trump was going to do anything he said he was going to do to help them? I’ll give an analogy: I remember going to see professional wrestling when I was 18 — wonderful entertainment, obviously rigged. The thing that astounded me as I looked around Colston Hall in Bristol is that quite a lot of the audience thought what they were seeing was for real. That’s what’s incredible to me about such a large swath of the American people: They can’t see that Trump is fake. And if they can’t see that when it’s right in front of them, how can you convince them of anything critical about the man? It’s like holding up a red sign to a person and the person says it’s blue. You can’t logically argue them into seeing red. The inability of people unable to intuit what was going on with Trump — I was impressed by it, not repelled. It was extraordinary to me that people couldn’t see how clueless he is.

Tell me more about your impression of Trump.

What also appalls me is the language of him and his cronies — people talking about sucking on their own cocks and such. I don’t know if it’s universal or distinctly American, but the vulgarity of the language of powerful men: It all comes down to penises and pissing and cocks. They talk like out-of-control 6-year-olds. I was thinking yesterday about a Chinese blessing. Can you guess which one?

May you live in interesting times?

Close. That’s the curse. The blessing is to live in uninteresting times. But I’m glad to be alive now. I wouldn’t swap these times for any other, because even though the whole world is a complete madhouse, it’s never been more interesting to me, even if stupidity has become rampant.

I was just looking back at some old Monty Python photos from the early ’70s, and it struck me that while the other guys sort of looked like rock stars with long hair and groovy clothes, you had short hair and dressed conservatively. Were you as engaged with the politics and social dynamics of that period as you seem to be with what’s going on today?

Oh, I was interested in a lot of the ’60s and ’70s but not the counterculture. Where I grew up, in Weston-super-Mare, our life was very proper and middle class. So the counterculture was very much counter to my culture. I never read Jack Kerouac or anyone like that. I just wasn’t terribly interested. I did find, though, that on the West Coast of America there were a lot of people who, like myself, do not like the materialist reductionist view of the world. I was more interested in that than I was in Haight-Ashbury, though Haight-Ashbury is somewhere I would’ve liked to visit.

That’s interesting, because there was always such a strong link between rock culture and Monty Python: John Lennon said he would’ve loved to have been in Monty Python and I know that members of Pink Floyd and Led Zeppelin helped finance Monty Python and the Holy Grail. The admiration there wasn’t reciprocal?

I didn’t know at the time that John Lennon was a fan. But I’m very strange about music, and for some reason I don’t really like rock, which is almost heresy. I remember coming back home once when Python were on tour — I think we’d just been in Newcastle — and the next morning Eric Idle said, “I went out to a dinner and David Bowie was there!” He was really excited. But if someone had said to me, “Want to come and meet David Bowie?” I would’ve just thought, why? I didn’t quite understand the assumption that I had an affinity for the counterculture.

Maybe it’s because the Ministry of Silly Walks and Dead Parrot sketches seemed like they could only have been the product of someone who was stoned.

Yeah, there were a lot of people that thought we were on pot when we were writing.

Were you?

No, and the suggestion vaguely irritated me. A prim part of me wanted someone to acknowledge that the humor we were doing in Python was quite clever, and instead it was always “oh, you obviously must just smoke pot and go crazy.” I’d think, Well, no, it’s a bit more skillful, actually. It requires more thought than that. [Graham] Chapman and I would spend an entire day deliberating over the right word for a sketch.

Does a different kind of person prefer Fawlty Towers to Monty Python? There are so few comedic similarities between the two.

There’s tremendous overlap of fans, but, you see, there are some people who just don’t get Python and I think that’s a function of education. There’s some subtle stuff that makes Python as funny as it is, and you have to be able to catch it. The thing about Fawlty Towers is that almost anyone can understand the comedy of it. It’s just about people getting frightened or scared or trying not to get blamed. A child of 8 can follow everything in it.

The emotion in Fawlty Towers is so much more acute, though. Basil Fawlty’s behavior makes me cringe in a way that nothing in Monty Python does.

People get embarrassed when they watch Fawlty Towers. I was in a therapy group once with a judge; when he joined the group he had no idea who I was. Most of the other people in England at that time would have some idea but he didn’t. When I told him what I did for a living, he said he’d watch Fawlty Towers. When I saw him next he said he’d started to watch it and had become so embarrassed by everybody’s behavior that he had to leave the room. The vicarious embarrassment was too much for him. I thought that was just perfectly funny.

That’s the second time you’ve mentioned therapy. Does the fact that you’ve been married four times suggest the limits of the practice for you?

I don’t know how to answer that. I think as you go along with therapy, you gain insight into yourself, hopefully, and also into other people, and you begin to see that there are better ways of handling both yourself and of handling other people.

Has being in therapy for so many years affected your work?

Certainly. I had a very friendly argument about a year or two ago with [Terry] Gilliam, because he felt that becoming more self-aware made you less creative. I said no, it makes you more creative but less productive.

Why less productive?

Because you become less driven. The neuroses and anxieties that make you driven become reduced.

I have another perhaps slightly morbid question, if you don’t mind.

Why stop now?

Excellent. Just last night, I reread the infamous eulogy you gave at Graham Chapman’s funeral. Have you ever wondered what the other Pythons might say at your funeral?

Yes, I have, and I don’t think it would be particularly complimentary. I mean it would be affectionate, but we’re like brothers who squabble and fight and a vast majority of it is pretty good-natured. Gilliam and I pretend to hate each other more than we do.

So many books you read about Monty Python — including ones written by members of the group — suggest that the other guys found you controlling. Is that characterization fair?

Those things usually come from Gilliam and am I right in thinking he’s a film director? Am I right in thinking that film directors are among the greatest control freaks on Earth? So there might be a bit of denial and projection going on. Gilliam is one of the worst judges of psychological matters I’ve ever come across. He’s very intelligent in a lot of areas, but psychologically he just doesn’t get it. If he experiences me as controlling, it probably just meant that I had different ideas from his. And you can ask Terry Jones about controlling, because while we were making Holy Grail, he and Gilliam were supposed to be directing it together, but they would sneak into the editing room at night when the other one wasn’t around and change things. That’s controlling.

So “controlling” was just the other Pythons’ word for when you expressed opinions?

The thing about my being controlling is there were times that we would do stuff and I’d say, “I don’t think that’s funny.” Is that controlling? Because if expressing an artistic disagreement to people who are about to do something that you don’t think is good enough is being controlling, then perhaps I am. And we did used to squabble about scripts, but I cannot remember a nasty fight about who should play what part. In all the Python years I can’t remember that kind of argument.

Were you inflexible?

Perhaps to a degree. I was much more rigid in those days about what constituted good comedy. But a lot of younger people are a bit rigid about what they think is good.

I was struck by a paragraph near the end of your memoir where you describe looking out from backstage at the massive crowd at one of the massive Monty Python reunion shows in 2014, and you recalled feeling no excitement in that moment. Does that mean you were ambivalent about the reunion?

That’s been misunderstood, including by Michael Palin. Eric and I were briefly keen to do a tour after those reunion shows and Palin didn’t want to do it. That was okay, you can’t force people to do things they don’t want to do, but when we asked him why he was opting out he said he had other plans. Fine, but then I think he felt guilty about saying no and started suggesting that the reason we didn’t go on tour was that I didn’t enjoy the reunion shows. That wasn’t what I’d said. I’d said I wasn’t excited by it. I enjoyed it a lot. I make a distinction between being excited and being happy. There’s a moment of excitement in creative things, which is where the addiction to doing them comes from. When Chapman and I suddenly saw the comic possibilities of an idea, the excitement was like a shot of something very special. Happiness is something else. I’m happy when I’m eating a wonderful meal, but I’m not excited by it.

Would you be happy, then, performing with some version of Monty Python again?

I’m sure, but maybe this helps: If I didn’t get a buzz out of 20,000 people watching me at the reunion shows, then that says something about my attitude to performing. Does that make sense? Today I can say that Monty Python ended in a very satisfactory way, and the ending taught me something about performing, which is that it doesn’t give me a high like the writing can.

Have you seen Terry Jones since he was diagnosed with dementia?

I haven’t seen him for quite a long time. I saw him at a funeral probably 18 months ago. And he … he’s not getting any better. He has a full-time caregiver, he goes for walks, enjoys his food, he can watch things on the box and read, but he can’t adjust to a conversation. He can be going down one conversational track and if you say something that’s not on that one track he derails. It’s very sad. He’s a sweet guy, and very talented.

You also wrote in your memoir — just in passing — that you believe you’re considered passé in England. Why is that the case?

Deliberate neglect by the press. Once you’ve made a name for yourself, which I did a long time ago, the British press will always try to cut you down. And also, which is very strange, the BBC hasn’t put Python out for years. In America, the younger generations keep rediscovering us and here it’s gone quiet. It’s ludicrous: We’ve done something that is basically recognized all over the world as being special and, to give one example, during the run of the reunion shows, a British paper ran a piece asking, “Is Monty Python really funny?” Not for everyone, no; but for an awful lot of people, yes. That ingrained negativity toward us is quite different from the rest of the world, who still see it as important and not just historical.

Can you see Monty Python’s influence anywhere? The work you did together has obviously lasted, but even though you’ll read things like how Lorne Michaels originally envisioned Saturday Night Live as a cross between Monty Python and 60 Minutes, it doesn’t feel like you can point to very much post-Python comedy that really displays the group’s sensibility.

I don’t see our influence. When I look at English comedy, which I don’t do very often, I never really saw any Python in it. I don’t know why there aren’t at least more attempts to copy us. Not that it bothers me — it puzzles me, because it violates the rule that if you do something successful then people will try to replicate it. When I was in the midst of Python, and even for a while after, I used to watch other comedy very carefully to see who was coming up on the rails. I was interested in seeing if there was good competition coming along, and there never was.

Were you a fan of Saturday Night Live?

I liked it. They asked me to host it, but I used to be much too purist. I never wanted to do a show where you had to rehearse an hour and a half of stuff in a single week. I don’t believe you can do all the material well given that deadline. So I declined offers from them two or three times.

You and Palin did eventually do the Dead Parrot sketch on Saturday Night Live, though. How’d that come about?

Only because we wanted to publicize something, I’m sure. We did the Dead Parrot sketch in some strange corner of the studio where the audience couldn’t really see us properly. We’d asked the show to let us do new material and they said no. I remember Michael and I were sitting at a steakhouse in New York with our wives before the show trying and failing to recall lines from the sketch. I said to him, “Do you realize we could go out onto the pavement and stop people and they could tell us the lines? But we just don’t know it anymore.” Of course, the sketch went down like a lead balloon.

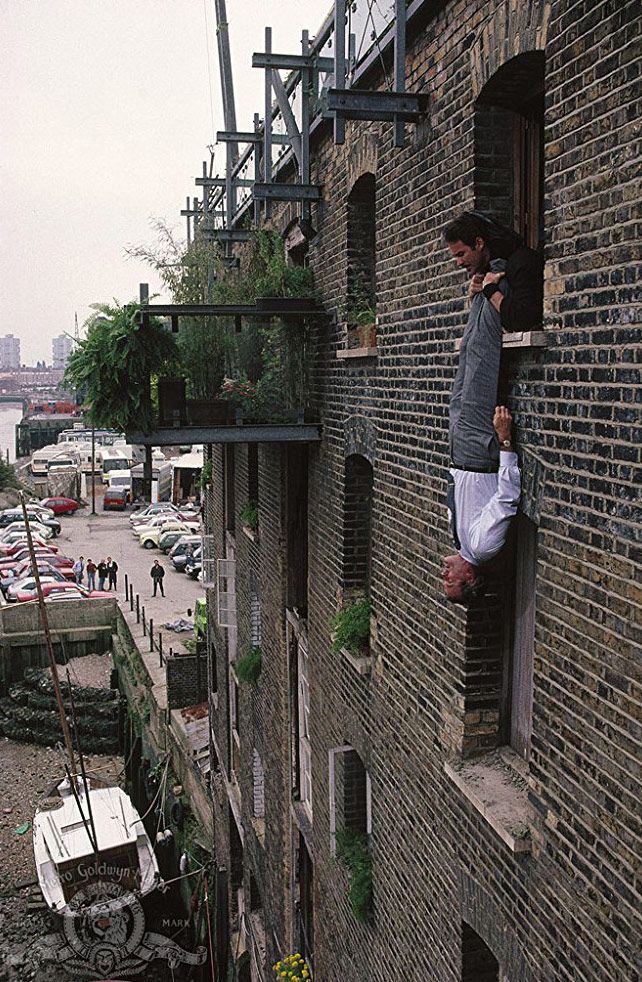

On the idea of success breeding copycats, I’m curious about whether or not after A Fish Called Wanda you had Hollywood opportunities that you never followed up on? Looking back at your filmography, there’s no clear sense that you tried to capitalize on how well that film did for you.

One of my sadnesses is that I had a real Hollywood moment and didn’t take advantage. I’m just remembering something from that time: I was in the swimming pool at the Four Seasons and they brought to me one of those old mobile phones, one of the huge ones. I took the call and it was Frank Oz, in London, offering me Michael Caine’s part in Dirty Rotten Scoundrels. My second marriage was a mess, and I thought, Can I really go off and do a movie without resolving whether I was going to stay married or not? So I turned the part down. I think if I’d done it, I would’ve gotten lots more Hollywood offers. Around Wanda I was hot for a year or so, but having a chaotic private life takes its toll. I also just didn’t have a sufficient commitment to film. I feel dead sitting in a trailer waiting for things to happen. I remember one of my friends, Michael Winner, saying to me back then, “typical Englishman: you have a big hit and then you go off and sit on the top of a mountain instead of getting on with another movie.” That was true. That’s what I did.

Certainly as far as American audiences are concerned, you’re best known for Monty Python, Fawlty Towers, and A Fish Called Wanda. Is there a correlation between the work you’re known for and the work you’re proudest of?

Work and notoriety is a funny thing. It has always seemed to me that there are two types of work. One is the work you do because you need money, and there’s another kind of work — a more enjoyable kind where money is absolutely not the key thing. When I’ve worked for money it’s been fine, but I don’t often feel anything like as involved as when I do things that were not for money. But, you see, after that very expensive divorce I mentioned earlier, I was basically forced to go and earn money. I had to earn $20 million, and you don’t get that sitting around drinking coffee and reading a good book. So I went off and I did all these one-man shows and I enjoyed it, but if I hadn’t needed the money I wouldn’t have done it. Instead I’d have gone off and written something that was more original. But I needed the money.

What are you working on now?

I have a show I’m working on at the moment called Why There Is No Hope.

Sounds funny.

It is funny. Some people immediately see the title as funny and other people go what?! There is no hope that we’ll ever live in a rational, kind, intelligent society. To start, most of us are run by our unconscious and, unfortunately, most of us have no interest in getting in touch with our unconscious. So if the majority of people are run by something they don’t know anything about, how can we have a rational society?

This reminds me of a popular YouTube video of yours where you talk about the problem of stupid people being too stupid to know that they’re stupid.

Yes. It’s the Dunning-Kruger effect. Put aside intellectually smart, the trouble is that most people aren’t even emotionally smart. They can’t deal with reality. If they’re not doing well, they’ll blame someone else. That’s why I have no hope of our ever having a proper, well-organized, fair, intelligent, kind society. We have to let go of that idea. It is possible that in some small area you can improve things temporarily. Swedish tennis is an example of that.

You mean the years from the beginning of Borg’s career to the end of Edberg’s?

Yes, Sweden had that extraordinary crop of tennis players for 20 years and it’s been nothing for them since. So now and again, like with Sweden and tennis, you can get an area where the whole thing works very well. But there’s no way to sustain it because people have no control over their egos and don’t understand — or don’t care — how their egos are distorting their thinking. Things always fall back into chaos. Which is why there is no hope.

There’s absolutely nothing that gives you any hope about the future of human society?

Nothing.

Nothing?

Nothing.

So why get up in the morning?

Just because you can’t create a sensible world doesn’t mean you can’t enjoy the world you’re in. I think Bertrand Russell once said that the secret to happiness is to face the fact that the world is horrible. Once you realize that things are pretty hopeless, then you just have a laugh and you don’t waste time on things that you can’t change — and I don’t think you can change society. I’ve spent a lot of time in group therapy watching highly intelligent, well-intentioned people try to change and they couldn’t. If even they can’t change …

As someone who’s spent a lifetime working in and thinking about comedy, is there one joke you can point to as being the funniest thing that you ever said?

Interesting. It would probably have been something unscripted. Eric Idle and I were performing in Florida once, taking questions from the audience, and a woman stood up and asked me, apparently seriously, “Did the Queen kill Princess Diana?”

What’d you say?

Certainly not with her hands.

This interview has been edited and condensed from two conversations.

Annotations by Matt Stieb.

In this 1988 hit comedy co-written by Cleese, he plays a lawyer who defends a diamond thief betrayed by his crew after a heist. He won a BAFTA for Best Actor, and earned an Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay.

Sitting on the Bristol Channel in southwest England, Weston-super-Mare is home to 76,000 residents, the Helicopter Museum, and a popular beach for middle-class day-trippers.

Reductive materialism suggests that only the material world exists and that all observations in the universe can be explained by physical reactions. For example, a reductive materialist would consider love to be the result of chemical firing in the brain.

In a radio interview, a revved-up Lennon said, “Part of me would sooner have been a comedian, I just don’t have the guts to stand up and do it. But I’d love to be in Monty Python rather than the Beatles. Fawlty Towers is the greatest show I’ve seen in years.”

In this 1988 hit comedy co-written by Cleese, he plays a lawyer who defends a diamond thief betrayed by his crew after a heist. He won a BAFTA for Best Actor, and earned an Oscar nomination for Best Original Screenplay.

Sitting on the Bristol Channel in southwest England, Weston-super-Mare is home to 76,000 residents, the Helicopter Museum, and a popular beach for middle-class day-trippers.

Reductive materialism suggests that only the material world exists and that all observations in the universe can be explained by physical reactions. For example, a reductive materialist would consider love to be the result of chemical firing in the brain.

In a radio interview, a revved-up Lennon said, “Part of me would sooner have been a comedian, I just don’t have the guts to stand up and do it. But I’d love to be in Monty Python rather than the Beatles. Fawlty Towers is the greatest show I’ve seen in years.”

Monty Python’s best-known film follows King Arthur and his knights through medieval perils and a maze of absurd events — a monster stops pursuit when his animator suffers a heart attack, and the knights are arrested by modern police for killing a historian documenting their quest. It’s the source of countless Python bits — coconut halves imitating horses galloping, the knights who say “Ni,” the airspeed velocity of an unladen swallow — and considered one of the best comedies ever written.

Chapman played the lead in Holy Grail and Life of Brian, struggled with a destructive alcohol problem, and was one of the few openly gay actors at the time, coming out in 1972. At his funeral in 1989, Cleese gave a moving, hysterical eulogy for his friend. “I guess that we’re all thinking how sad it is that a man of such talent, of such capability for kindness, for such unusual intelligence, a man who could overcome his alcoholism with such truly admirable single-mindedness, should now so suddenly be spirited away at the age of only 48 before he’d achieved many of the things in which he was capable, and before he’d had enough fun. Well, I feel that I should say, ‘Nonsense! Good riddance to him, the freeloading bastard. I hope he fries.’ And the reason I feel I should say this is he would never forgive me if I didn’t. If I threw away this glorious opportunity to shock you all on his behalf. Anything for him but mindless good taste.”

Monty Python’s best-known film follows King Arthur and his knights through medieval perils and a maze of absurd events — a monster stops pursuit when his animator suffers a heart attack, and the knights are arrested by modern police for killing a historian documenting their quest. It’s the source of countless Python bits — coconut halves imitating horses galloping, the knights who say “Ni,” the airspeed velocity of an unladen swallow — and considered one of the best comedies ever written.

Chapman played the lead in Holy Grail and Life of Brian, struggled with a destructive alcohol problem, and was one of the few openly gay actors at the time, coming out in 1972. At his funeral in 1989, Cleese gave a moving, hysterical eulogy for his friend. “I guess that we’re all thinking how sad it is that a man of such talent, of such capability for kindness, for such unusual intelligence, a man who could overcome his alcoholism with such truly admirable single-mindedness, should now so suddenly be spirited away at the age of only 48 before he’d achieved many of the things in which he was capable, and before he’d had enough fun. Well, I feel that I should say, ‘Nonsense! Good riddance to him, the freeloading bastard. I hope he fries.’ And the reason I feel I should say this is he would never forgive me if I didn’t. If I threw away this glorious opportunity to shock you all on his behalf. Anything for him but mindless good taste.”

The formally elegant, 12-episode BBC Two sitcom (the first six-episode season aired in 1975; the second in 1979) takes place in a hotel on the English Riviera, where Cleese plays the beleaguered Basil Fawlty, an innkeeper constantly on the verge of a meltdown.

The only American-born member of Monty Python, Gilliam drew the troupe’s intersketch, Dalí-esque cartoons, and generally played the parts no one else wanted to, like the knight in armor with the whole chicken that ended sketches. After co-directing Holy Grail with Terry Jones, Gilliam went on to direct postmodern mousetraps like Brazil, 12 Monkeys, and the adaptation of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

Jones had a gift for physical humor, and was the go-to Monty Python member for drag, like the beloved Spam-lady. After directing Holy Grail and The Meaning of Life, Jones hosted BBC history documentaries and wrote prolifically against the Iraq War. In September, 2016, Jones announced that he had been diagnosed with dementia and was no longer able to give interviews.

The formally elegant, 12-episode BBC Two sitcom (the first six-episode season aired in 1975; the second in 1979) takes place in a hotel on the English Riviera, where Cleese plays the beleaguered Basil Fawlty, an innkeeper constantly on the verge of a meltdown.

The only American-born member of Monty Python, Gilliam drew the troupe’s intersketch, Dalí-esque cartoons, and generally played the parts no one else wanted to, like the knight in armor with the whole chicken that ended sketches. After co-directing Holy Grail with Terry Jones, Gilliam went on to direct postmodern mousetraps like Brazil, 12 Monkeys, and the adaptation of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

Jones had a gift for physical humor, and was the go-to Monty Python member for drag, like the beloved Spam-lady. After directing Holy Grail and The Meaning of Life, Jones hosted BBC history documentaries and wrote prolifically against the Iraq War. In September, 2016, Jones announced that he had been diagnosed with dementia and was no longer able to give interviews.

In July 2014, the surviving members of the troupe put on the greatest-hits show Monty Python Live (Mostly) at The O2 Arena in London, in part to pay legal fees and royalties owed to Holy Grail producer Mark Forstater. The performances were a massive success with fans.

Palin often played the straight man to Cleese’s meltdown characters, and was featured in some of Monty Python’s most famous sketches, including Dead Parrot and the Spanish Inquisition. After Python, he worked on several of Terry Gilliam’s films including Brazil, won a BAFTA for his role in A Fish Called Wanda, and hosted a series of BBC travel docs.

In July 2014, the surviving members of the troupe put on the greatest-hits show Monty Python Live (Mostly) at The O2 Arena in London, in part to pay legal fees and royalties owed to Holy Grail producer Mark Forstater. The performances were a massive success with fans.

Palin often played the straight man to Cleese’s meltdown characters, and was featured in some of Monty Python’s most famous sketches, including Dead Parrot and the Spanish Inquisition. After Python, he worked on several of Terry Gilliam’s films including Brazil, won a BAFTA for his role in A Fish Called Wanda, and hosted a series of BBC travel docs.

In 1997, promoting the Wanda follow-up Fierce Creatures, John Cleese and Michael Palin reprised their classic Dead Parrot skit to a dead audience on SNL. Palin later wryly explained the silence by saying that the audience was mouthing the words to the sketch.

Oz directed Dirty Rotten Scoundrels and Death at a Funeral, though he may be more famous for his work as a puppeteer. He brought to life characters like Miss Piggy and Fozzie Bear on The Muppet Show, Cookie Monster and Bert on Sesame Street, and was the puppeteer and voice of Yoda.

Michael Caine and Steve Martin play English and American con men in the French Riveria who agree to a gentleman’s bet: The first person to swindle $50,000 from a mark can stay, the other must skip town. Caine was nominated for a Golden Globe for his role, and the comedy was a hit, earning $42 million at the box office.

Winner directed the Charles Bronson vigilante-action trilogy Death Wish, and was a restaurant critic for the Sunday Times.

Cleese has a stormy relationship with relationships. In 1968, he married Fawlty Towers actress and co-writer Connie Booth and divorced a decade later. In 1981, he married Rollerball actress Barbara Trentham, and divorced in 1990. In 1992, Cleese married psychotherapist Alyce Faye McBride, whose divorce in 2008 cost him a £12 million settlement — he joked that his subsequent one-man show was his “Alimony Tour.” Cleese married his current wife, jewelry designer Jennifer Wade, in 2012.

A psych theory for our time, the Dunning-Kruger Effect is a cognitive bias where people who are inept at a certain task are unable to realize their own ineptitude.

From 1974 to 1992, Swedish men won 24 out of 76 Grand Slam events, a bonkers run for a country with a population a little greater than New Jersey. Sports historians are fascinated by the rise and fall of the brief tennis powerhouse.

The 20th-century philosopher, logician, and Nobel winner had an outsized effect on linguistics, artificial intelligence, and computer science.

Idle was Monty Python’s musical genius, who wrote “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life” and the 2004 musical Spamalot, which won three Tonys, including Best Musical, and grossed over $175 million.

Conspiracy theories abound 20 years after her death: The British Secret Intelligence Service blinded Diana’s driver with a strobe light causing the crash; the Royal Family arranged the crash so she wouldn’t marry her megarich Egyptian boyfriend; the EMTS intentionally botched her treatment before she arrived at the hospital.

In 1997, promoting the Wanda follow-up Fierce Creatures, John Cleese and Michael Palin reprised their classic Dead Parrot skit to a dead audience on SNL. Palin later wryly explained the silence by saying that the audience was mouthing the words to the sketch.

Oz directed Dirty Rotten Scoundrels and Death at a Funeral, though he may be more famous for his work as a puppeteer. He brought to life characters like Miss Piggy and Fozzie Bear on The Muppet Show, Cookie Monster and Bert on Sesame Street, and was the puppeteer and voice of Yoda.

Michael Caine and Steve Martin play English and American con men in the French Riveria who agree to a gentleman’s bet: The first person to swindle $50,000 from a mark can stay, the other must skip town. Caine was nominated for a Golden Globe for his role, and the comedy was a hit, earning $42 million at the box office.

Winner directed the Charles Bronson vigilante-action trilogy Death Wish, and was a restaurant critic for the Sunday Times.

Cleese has a stormy relationship with relationships. In 1968, he married Fawlty Towers actress and co-writer Connie Booth and divorced a decade later. In 1981, he married Rollerball actress Barbara Trentham, and divorced in 1990. In 1992, Cleese married psychotherapist Alyce Faye McBride, whose divorce in 2008 cost him a £12 million settlement — he joked that his subsequent one-man show was his “Alimony Tour.” Cleese married his current wife, jewelry designer Jennifer Wade, in 2012.

A psych theory for our time, the Dunning-Kruger Effect is a cognitive bias where people who are inept at a certain task are unable to realize their own ineptitude.

From 1974 to 1992, Swedish men won 24 out of 76 Grand Slam events, a bonkers run for a country with a population a little greater than New Jersey. Sports historians are fascinated by the rise and fall of the brief tennis powerhouse.

The 20th-century philosopher, logician, and Nobel winner had an outsized effect on linguistics, artificial intelligence, and computer science.

Idle was Monty Python’s musical genius, who wrote “Always Look on the Bright Side of Life” and the 2004 musical Spamalot, which won three Tonys, including Best Musical, and grossed over $175 million.

Conspiracy theories abound 20 years after her death: The British Secret Intelligence Service blinded Diana’s driver with a strobe light causing the crash; the Royal Family arranged the crash so she wouldn’t marry her megarich Egyptian boyfriend; the EMTS intentionally botched her treatment before she arrived at the hospital.