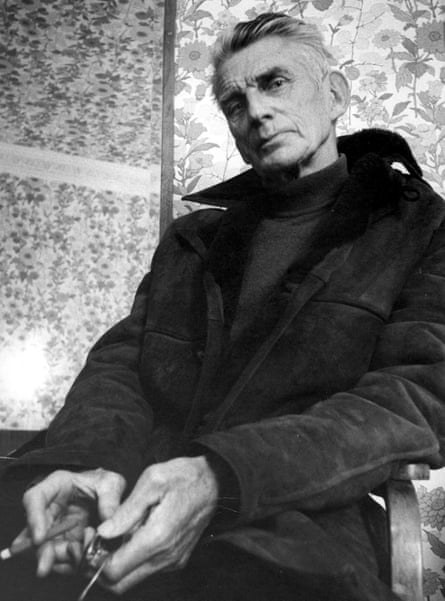

Anyone who has seen Barry McGovern’s solo show Watt or caught him in multiple versions of Waiting for Godot – where he has played three of the five characters – will know that he is a consummate Beckett actor. It is no surprise, therefore, to discover that he is superb in Michael Colgan’s musically precise production of Krapp’s Last Tape which, playing at the Church Hill theatre, shines like a gem at this year’s Edinburgh international festival.

Why, though, are we so happy to return to this particular play? Even to someone like myself, who is not a fully paid-up member of the Beckett club, the work never ceases to astonish.

It is partly because of its perfect alliance of form and content. As we watch the 69-year-old Krapp hunched over a tape recorder, listening to the voice of his 39-year-old self, we encounter a work that counterpoints present pain and past happiness and that combines grief and lyricism. It is something we can all relate to.

At the same time, it is an exercise in self-revelation. For Beckett, it is clearly a portrait of the artist as an old man who has fatally sacrificed love for a life of futile scribbling. Beckett may have become a global phenomenon but he understood the wretchedness of a writer whose “opus magnum” sold 17 copies, “of which 11 at trade price to free circulating libraries beyond the seas”.

McGovern, however, brings to the role his own special gifts. His Irish speech rhythms lend the passages of erotic reverie, where Krapp recalls lying in a punt with a lost love, the sensuality of a male Molly Bloom. Without overdoing the clowning, McGovern also conveys Krapp’s absurdity: having assiduously avoided one discarded banana-skin, he slides helplessly on a second. There is rich comedy too in the way McGovern silently mouths the word “viduity” which he scuttles to a dictionary to define only to find the book is upside down. Above all, McGovern captures the divided nature of a man who regards his “muckball” of a life with a mixture of derision and regret. Krapp’s vow to renounce drinking is greeted with the embittered laugh of a lifetime alcoholic yet, as he recalls past loves, McGovern’s hands embrace the tape-recorder as if it were a girl’s waist.

McGovern doesn’t overstress Krapp’s palsied age. Instead he gives us a recognisable human being confronting the desolate waste of his existence.

It is a magnificent performance and I found myself, Krapp-like, recalling past interpretations of the role. Even if some of Beckett’s later plays seem over-prescriptive, the genius of Krapp’s Last Tape is that, like an oldster’s Hamlet, it brings out the particular qualities of its performers.

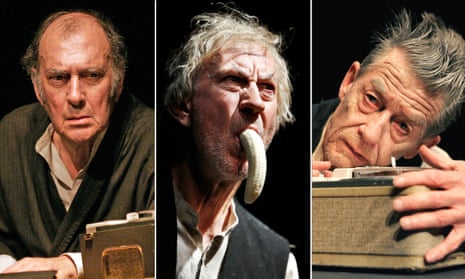

The first Krapp I saw was the great German actor Martin Held in Beckett’s own production in 1971: I can’t improve on Irving Wardle’s description of the contrast between Held’s grotesque, hobbling gait and total precision when he reached his table and the spools of tape that were his surrogate children. Two years later, I saw a totally different performance from Albert Finney at the Royal Court. According to Beckett’s biographer, James Knowlson, the dramatist thought Finney miscast and there is no doubt that, at 37, he was absurdly young to play the role. Yet, although Finney had to act senility rather than embody it, I’ve never forgotten his capacity to convey pain: as he listened to Krapp’s recollection of love-making, Finney’s head sunk into the crook of his arm and he emitted animal-like mews and sobs.

When Max Wall played Krapp at Greenwich theatre in 1975, he had two obvious advantages: he was both a life-battered comic and was directed by Patrick Magee, whose voice inspired Beckett to write the play. Wall also loved language and when he uttered the word “spool” he voluptuously extended the vowel and flung his arms wide in recollected happiness. Much later, in 1999, I saw John Hurt as Krapp and, with his seamed features and close-cut, iron-grey hair, he strongly resembled Beckett himself while investing the role with his own sense of wounded vulnerability.

And then, in 2006, unforgettably there was Harold Pinter. Forced by illness to play the role in a motorised wheelchair, Pinter stripped it of any sense of sentimentality and brilliantly brought out Krapp’s terror of the extinction he once craved. At two precise moments, Pinter gazed over his left shoulder into the circumambient darkness as if he felt death’s presence in the room. But that, finally, is a measure of the play’s greatness. It appeals to our own sense of mortality, waste and failure while taking on the lineaments, as McGovern now richly proves, of the actor who is lucky enough to play it.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion