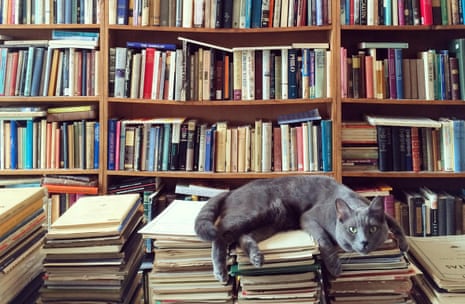

I recently had the privilege of circling the world to write a book about libraries. My timing was excellent: after a short-lived e-books scare, physical books are back in fashion, and libraries are the place to be.

My trip was not unlike the pilgrimages made by 18th-century library tourists. On my journey I noticed two trends that are changing how we think of old books and old libraries.

The first is a stronger focus on provenance research. Through whose hands have the books passed? How did those handlers use and mark and protect their books? This branch of bibliography is helping to humanise it.

The other trend involves breaking away from traditional ideas of what constitutes a meritorious book, and from the traditional oppositions of high and low literature. Thanks to this, pulp novels – featuring what Allen Lane called “bosoms and bottoms” cover art – have infiltrated rare book collections. Crime pulps and sci-fi paperbacks are now prized by such hallowed institutions as the Smithsonian, the Houghton and the British Library.

Old-school bibliographers and librarians would probably be mortified by the incursion of pulps, which are fighting not only for shelf space but also for influence. But instead of being corralled and appropriated into old models of scholarship and curation, the pulp sensibility is spreading. Traditional bibliography and librarianship are being reread and reshaped with a pulp mentality.

Pulps, in short, are about lust, sex, theft, betrayal and degradation. Pulp men and women are dangerous, duplicitous, damaged. What is coming from this Gonzo-esque rereading of books and their stories? A new history of old books that is human, messy, fascinating and appalling, shot through with desire and criminality, heroism and dereliction.

The history of libraries is rich with metaphors of books as lovers, prisoners, weapons, potions and creatures. It is also rich with real, non-metaphorical creatures. Much is known about the ecosystems and biodiversity of libraries. Library fauna such as bookworms, bedbugs and microbats have long been the subject of study. But a little-known subfield concentrates on the human biology of libraries.

When Sylvia Plath vengefully incinerated Ted Hughes’s personal papers, she sprinkled in his dandruff and fingernail cuttings. The Australian bookbinder and bibliophile Richard Griffin, after crashing his car into a tram, famously bled on many of his most precious books (Griffin’s girlfriend tried to drown some of the others in the bath).

Seventeenth-century books are now being searched for the DNA of Shakespeare – or perhaps of Francis Bacon, Henry Neville or Edward de Vere – to resolve the so-called Authorship Question. DNA testing has also been used in libraries to identify materials used in book-making. (French books covered with the skin of guillotined prisoners were said to be bound in “aristocratic leather”.)

People are present in their books in other ways, too. Books shape our characters and create us as subjects: consider the young Marquis de Sade consulting the dangerously formative library of his libertine uncle, the Abbé de Sade. Or the Welsh coalminer reading a blue Pelican for the first time and experiencing a political awakening.

The personalities and daily habits of 19th-century bookmen such as Thomas Frognall Dibdin were inseparable from the ardent love of books. More recently, John Charles Gilkey used stolen cheques and credit card numbers to buy books so he could be a proper gentleman with a proper gentleman’s library, like the ones he saw in Sherlock Holmes films.

Books can capture our souls in a benign way. Consider the monks enthralled in the holy work of manuscript illumination. Or Jack Kerouac and the Marquis de Sade pouring their passions into their scroll manuscripts. How did Thomas Carlyle feel when the solitary draft of his history of the French revolution was accidentally destroyed? “I just felt,” he told Tennyson, “like a man swimming without water.”

The history of libraries is full of remarkable discoveries, often of scandalous books – such as Richard Heber’s exceedingly rare copy of Sodom, or the Quintessence of Debauchery; and found in the Vatican, The Secret History, which revealed the depraved life of the emperor Justinian and his wife, Theodora.

In private libraries, books share our most intimate moments. Jeanette Winterson hid Freud and DH Lawrence in her knickers so she could read them on the toilet. Many bibliophiles have chosen to die with their books. Many heretics have died with their books involuntarily. After the 1652 looting of the great Mazarin library, its custodian, Gabriel Naudé, cried in anguish, for he loved the library “as a father loves his only child”.

The destruction of books has become a staple of literature. Books are burned in Don Quixote, Fahrenheit 451, The Dream of Scipio, Anne of Green Gables and all the Pepe Carvalho novels of Manuel Vázquez Montalbán. Despite these multiple occurrences, book burning still carries an intense emotional power.

In Dreamtigers, the author-librarian Jorge Luis Borges wrote a parable about a man who spends his life travelling the world. From the places he visits, the traveller collects a jumble of images – animals, landscapes, machines, stars, fellow travellers. Finally, as his death approaches, he realises the collection of images has made a composite picture – of his own face.

Only after I’d finished my library tour and my book could I see the image that emerged from the pulpy jumble of bookish stories. The picture is nothing less than a new understanding of what libraries are for – not art, architecture, education, politics, antiquarianism, digitisation or information science. Instead, it is about humanism and self-preservation.

The composite picture is one of libraries that contain our flesh, our selves and our souls. Why do we flinch so when books are burned? Because the books are us.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion