On Tuesday morning, Peter Barbey, owner of the Village Voice, assembled the staff of the storied but turbulent New York City alt-weekly for a meeting. The paper, he said, would cease print operations for the first time since its founding in 1955, but will continue to publish digitally. When the last print issue would hit the red honor boxes wasn't made clear. The meeting lasted about three minutes. None of the surprised staff asked any questions. A press release went out, and then employees dispersed back to their desks, uncertain about their own immediate future in an even more uncertain media climate.

"I think everybody was stunned," film editor Alan Scherstuhl told Esquire. "You know how you always expect this will be the last month things keep going? Everybody is kind of surprised, but also like, 'I can't believe we got away with it this long.'"

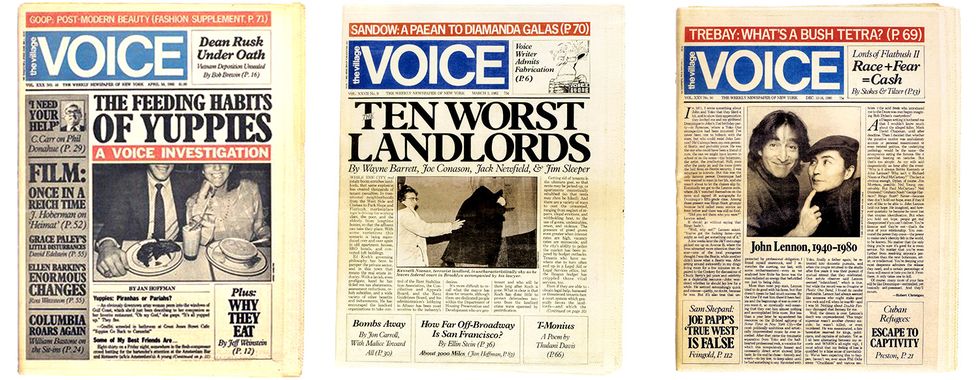

The news comes after more than a decade of the paper toggling between owners, mergers, and separations. But for all the specific changes at the Voice itself, there is a bigger problem across the media in general: declining ad revenues, and, in particular for alt-weeklies, the full-scale migration of classified ads from print to the internet. The Voice's future as a newspaper may have just reached its denouement, but it's been a long time coming.

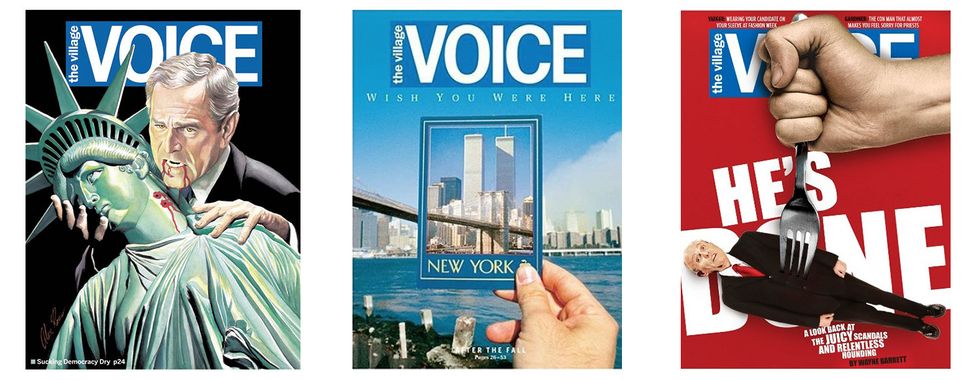

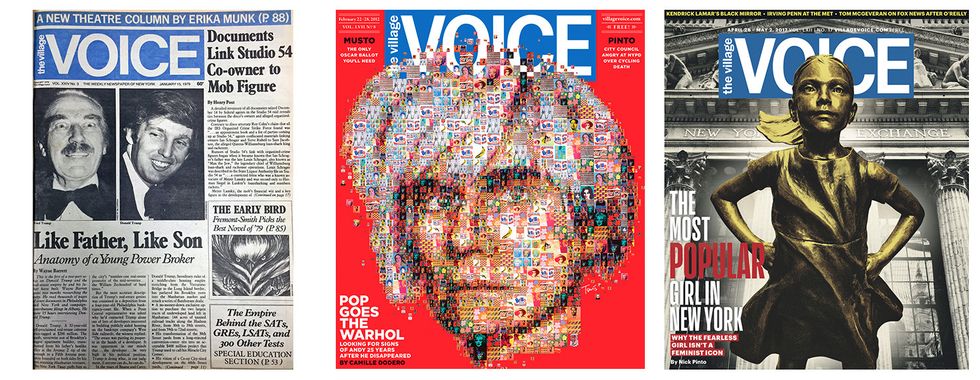

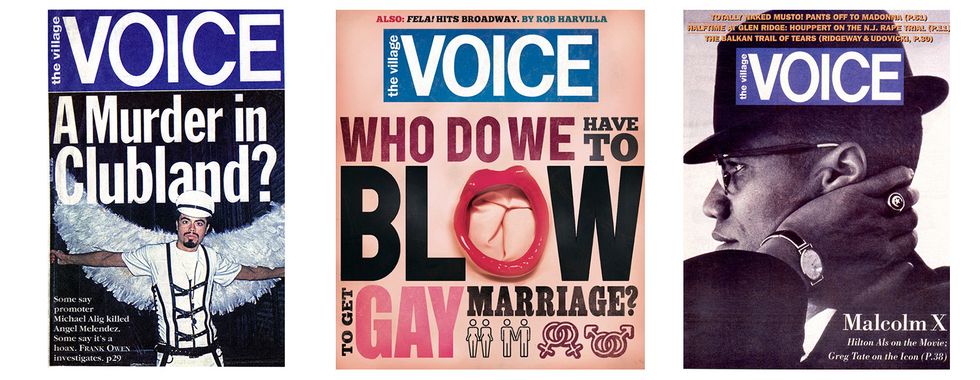

The Village Voice was the publication that invented the concept of the alt-weekly newspaper, and indeed much of the irreverent, speaking-truth-to-power brand of journalism that we take for granted today. (Ironically, the news came on the one-year anniversary of the end of Gawker, a spiritual nephew for the internet age.) For decades, the Voice set the agenda for the cultural calendar of New York's underground music and arts scene, and influenced dozens of other papers around the country. For many who read the Voice it was a similar gateway, the definition of urban cool, and generations of young writers grew up fantasizing about seeing their byline printed on its pages. Many of those writers, including myself, eventually did, but the history of people who cut their teeth in the Voice is as impressive as any in American letters. A group of them, including Ta-Nehisi Coates, and Voice stalwarts Tom Robbins, Michael Musto, and Robert Christgau, recently signed onto a letter petitioning the paper to meet the conditions of the Village Voice Union, who were attempting to renegotiate their contracts, something that may or may not have factored into Barbey's decision, depending on whom you ask.

Neither the Voice's editor, Stephen Mooallem, nor Barbey immediately responded to Esquire's interview requests, but in a press release Barbey said:

"For more than 60 years, The Village Voice brand has played an outsized role in American journalism, politics, and culture. It has been a beacon for progress and a literal voice for thousands of people whose identities, opinions, and ideas might otherwise have been unheard. I expect it to continue to be that and much, much more."

Over the past 24 hours, I've reached out to writers and editors from multiple eras of the paper's existence to reflect on what the Voice meant for them, and the culture at large, based on their individual subjective memory. Excerpts of those conversations are below, lightly edited for clarity.

Robert Sietsema, food critic (1993-2013)

My era at the Voice was a time of tremendous changes in the world of journalism. Like riding a bucking bronco, I managed to stay on for 20 years even after New Times bought the paper and laid my colleagues off one by one. I thought I had a formula for staying onboard forever, but eventually they got me, too, and when they got me I was glad to leave.

I moved to New York in the '70s from Texas and had a $150 apartment. A lot of the people that wrote for the Voice lived in the Village. Now people can't afford to live here anymore. Eventually that takes its toll. Being in the center of things did have an effect on your ability to observe and go places at odd hours. To have publications that were tied to specific locales such as the Voice and to have consistent opinions and especially thought-out essays, those are not in as large supply anymore. Online publications seem to come from nowhere. They don't necessarily tie you to a place and its thought-processes and opinions. It's like living in a different universe and reporting on Earth to be so online.

The Greenwich Village that generated the Village Voice is long gone itself. What is perhaps sadder is journalism as a durable lifelong profession has been going down at the same time. Many young journalists I know are struggling to support themselves as journalists. The full-time, paying journalists jobs have disappeared one by one.

There's a lot of cultural writing going on online, much of it quite good, but having a group of distinctive voices all in one place, that was something that the print publication did well. Now journalists are kind of much more itinerant. Having that kind of platform like the Voice was a total boon to developing a career and having strong opinions and writing consistent work. I would at this point think very seriously about a career in journalism. It's more of a hobby now. That may eventually have an impact on our very democratic society.

Dan Perkins, Tom Tomorrow of This Modern World (1997-2006)

When I got in there, the Voice was the big time. If you were an alt-weekly cartoonist, that was the goal, the pinnacle of papers.

It's incredibly trite to say it, but it really does feel like the end of an era. But the Voice is a symbol. The Voice is huge. I don't live in New York anymore, so I don't read it regularly, but it feels like I just got the news somebody I used to be involved with passed away.

Thulani Davis, writer and editor (1978-1991; 2001-2004)

They wouldn't let me write about jazz because I had too many friends who played jazz. I got to discover reggae and rap. I was the first person to cover either of those things there. I saw Afrika Bambaataa, all those guys. I wrote my first review in rhyme. The first time I wrote a feature, I wrote about James Brown, and Nat Hentoff went around the building and asked who was I and went and told the editor, Whoever she is, keep her, she's great. He championed me through my first firing. He helped me get my first book published. Those people were awesome. The other thing I loved about the Voice was the art direction, the photographers, they made it beautiful.

When I was hired as an editor I was told point blank that in addition to editing whoever I edited, that my job was to get black writers, Asian-American writers, Latino writers. I was in charge of getting all the people of color. That is how this country works. If you write an anthology of literature, they'll call you up and say, Could you do the black chapter? The Voice came out of that same culture. That same intellectual New York culture where every set had one black person. Every school had one black person.

From Norman Mailer forward, they earned their mythology. At this point in time, I hope all the heirs to Wayne Barrett, Jack Newfield, Joe Conason, I hope they're working their butts off. The investigative end of the Voice is legendary for a reason. When Trump was coming near to the end of the campaign, it was ironic because they were calling Wayne who had written about him 20 years earlier. All of them mentored me in one way or another.

Camille Dodero, editor and writer (2007-2012)

From the time I was 19 years old, I had one concrete goal: To write for the Village Voice—and that was before I thought I would ever realistically be able to call myself a writer. I learned how to write in any publishable way by reading the Voice, and when it went online, then cutting-and-pasting Voice pieces into Word documents, so I could see how those sentences were assembled. So when I got the chance to work within earshot of someone like Tom Robbins, or serve on the union alongside the great J. Hoberman, or listen to Lynn Yaeger call out bullshit at meetings, or have Michael Musto crack withering jokes to me—their examples, as well as the towering legacy that stood before them, was everything to my development. That said, my story is no different than the hundreds of other writers and journalists who had the life-changing opportunity of working at the Voice and learning from many of the finest talents who've ever worked in non-fiction.

What I believe to be the most significant, perhaps symbolic, loss of the Village Voice's print arm—which I wrote about when the Boston Phoenix shuttered, for Gawker!—is that there are fewer and fewer pathways for kids from low-income families to become journalists. In my experience, the alt-weekly world famously recruited and mentored scrappy people like me, or like, say, David Carr, and there are few mechanisms left that are predisposed to bring that class of people into this world. If that continues to be the case, and we don't have people who identify with working-class, low-income people working on the national level, we'll get more and more dangerous surprises like the election of Donald Trump.

The alt-weekly's purpose was, in theory, speaking truth to power and the ability to be irreverent, and print the word "fuck" when doing so. Gawker was, in my view, a 21st-century extension of that same alt-weekly ethos. What conclusion can be drawn from the coincidental date of their deaths? Probably nothing but some bullshit about end of year projections and/or tax quarters that business savvy people unlike me could speak to.

Alan Scherstuhl, film editor for Voice Media Group (2012-present)

Working at the Village Voice has always been like Saturday Night Live, where everybody tells you what year they liked it, and yes there were some bad years. But even in its thinnest year there was excellent work in there.

Voice Media Group and the Village Voice have for five years given me freedom I thought didn't exist anymore in media to put together a film section I thought the world would never see again. We still have a five-six page film section, which, for an alt-weekly in 2017, is extraordinary. I have three full-time staffers plus me covering movies. That's rare.

The Village Voice writers have always had freedom to cover what they think is important. We've never been told to chase pageviews or to write about anything but what it is we're interested in, championing anything we want to champion. We've not run a Game of Thrones piece yet this year. We have not had to. I do recognize that is rare and that is potentially unsustainable.

Sasha Frere-Jones, writer (1994-2004; 2016-present)

They were doing a whole pull out post-rock supplement, and Ann Powers asked me to write about being in my band. After that, she asked me to do more, and that was the beginning of everything for me. I thought I was just in a band. It's one of those classic ready-mades like a Hollywood movie, where you look back on your career and say, I owe it all to somebody. But it's true. It's what I grew up on, so being able to write for them was a real joy. And being edited by those people kind of taught me a chunk of what I still know. The standards for editing and fact-checking were really high. From the beginning of my career, I had it in mind that everything in my piece was going to be pushed on, somebody was going to kick the tires. Every single tire. That's a mangled metaphor. All 1,500 tires.

The most New York thing of all is to say I read it when it was cool and then it became uncool. Everyone will have an uncool date. When I was growing up, it was by far the coolest thing in the world. I was very lucky to be a kid in the '70s and '80s, and the music writing team at that point, it felt like we had the 1977 Yankees. Greg Tate, Jim Hoberman, then in the '80s Joan Morgan. The quality of writing was so much higher. You'd read a mainstream newspaper review and it would feel like a book report: Here's what happened. You wouldn't get to know if someone loved it or hated it. You'd read a Voice review and it would be a fireball, full of references to things I never read, which is how I found out about so much. Editors say now people won't get that reference … how the fuck are you supposed to find out about new things then? I only read Marx because someone wrote about it in a Gang of Four interview. How would you find it otherwise? Why would you find it otherwise? It always seemed cool to me. I'm also really proud of being what it's been in the last year. It's pretty fucking cool now.

I was looking at the Google archive today, and I found an ad for DNA's very last show in 1982. I got this really intense ... those ads for the bands in the back? The only way you knew about a show was to wait for the Voice to come out. People didn't put up posters. CBGB didn't put out a letter board. They didn't have anything other than that ad in the Voice. I'm averse to the nostalgia thing. But I do think it helped bands, where a mundane thing, playing a show, became more magical because you spent most of your week not knowing, and now you knew. And now there's zero time that you don't know. You spend all of the time up to the show knowing. You had no idea you were seeing that band. In some ways, it was a cheap trick. You hide something and you reveal it, it's the essence of magic, of narrative really. That's a little bit of what we lost. That doesn't mean newspapers were better, but that was a sweet little thing about being able to experience things without over-thinking them. Is that a big deal? No. It was a pleasant thing.

When people get into the death of journalism thing it bums me out. It's more a modality that was pleasant is dying. Yes, it feels different to read in print. If you pick up the Voice or anything and go though whole thing you're definitely going to read things you don't read online. I don't know anyone who goes to a website and says Today I'm reading this whole website. You read about a book you didn't intend to or en exhibit. But that's something we're losing with or without the Voice.

Michael Musto, writer, (1984-2013; 2017-present)

I wasn't that shocked. I've been talking about it since the '90s: I wonder how all of print media could survive. Starting back then, the Village Voice started pumping up their web presence—they always valued the site—so that's a very good thing to have now to keep them relevant. But obviously there have been so many challenges, from real estate ads going elsewhere and hook-up arrangements going elsewhere, and the mass media seems to have subsumed the underground in some way. Combined with the fact that people want their information immediately, they don't necessarily need to wait 'til Wednesday. But the Voice has been very savvy to realize that.

I don't think we'll have print in the future, things have morphed into a different landscape and people have to adapt to it. (In Norma Desmond fashion, I still keep all my old clippings. But unlike Norma I never look at them.) It's nothing to get that concerned about. There's something about holding a publication in your hand and not missing out on anything because you're going page by page, but basically everything has adapted to a new medium. And there's more information now because the internet is infinite.

I'm old enough to remember when computers came around and people felt there was something lost in communing with your typewriter. I don't think anybody now wishes they had their old typewriter back. A lot of times we cling on to old habits because they're familiar and it's hard to adapt, but ultimately we don't look back with a lot of longing about old archaic ways of doing things.

Eric Sundermann, editorial assistant, (2012-2013)

It's had more of an impact on me than anything else I've done in my career. Working at a legacy publication—even just for a year, towards the end of its print life, among all the empty cubicles of people who'd been fired over the years—was still massively influential on the way that I think and approach editing and writing. I worked under Brian Parks, who was the arts editor at the time, and his care and appreciation for the written word is something I still feel in my daily work. I wouldn't be the editor or the writer I am today without him or the Village Voice.

What hurts the most about the Village Voice closing down its print is that it feels a bit like God died. The pages of the Village Voice—which I became very familiar with while sorting through the archives as an editorial assistant—were the blogosphere before the internet. There were sometimes typos, but the words jumped off the page as the publication embraced the angle of the people. The Voice was mad as shit, and unafraid of calling out bullshit—whether it was corrupt politicians or musicians who made shitty music. It was the voice of the people by the people. It captured the energy of New York City.

Steven Thrasher, staff writer (2009-2012)

The Voice was a real breeding ground for a number of significant black writers, Thulani Davis, Ta-Nehisi Coates. It's certainly a big influence in my world, in queer America. The Voice had the first reporters on ground for the Stonewall Rebellion, there are endless culture writers who have gone through there. It does have a really significant place in the thinking and writing of journalism and there is something special about it. But in the time I worked for it it was also very exploitative of talented writers, so I have mixed feelings.

I think it's very poetic that Gawker died a year ago today, and the Voice, to me, seems like it's dying today. When I wrote for the Voice we had kind of a moment of renaissance, we had some great writers, Jen Doll, Camille Dodero, were coming out of the era I was in. There was some joyful thing about writing for the Voice. It was sort of a punk place to work and openly critical of the dominant media culture and a lot of comfortable politicians, including politicians on the left even though it came from the left as well.

One thing, when I worked for the Voice, I appreciated being unionized. The connections I made out of that. I got a good severance when I got laid off. That was the last gig I had when there was any positioning of thinking people need a job, healthcare, retirement. That was the last time I even had the pretense of those things. I think we're really screwed in that so many publications don't have a long vision. We're screwed as journalists for thinking we can have long term jobs and career development.

Maura Johnston, music editor (2011-2012)

The Voice used to be a paper where, legend had it, people would crowd outside its office in order to be the first to snatch print copies so they could get first crack at apartment ads. When I would buy it for my train rides home to Long Island as a teenager and college student, it was huge—and it was a lot easier to pore over and unexpectedly find out about new things in both its editorial work and its ads, even if they were things I felt resistant to for whatever reason. So many crappily named bands played CBGB, Wetlands. The way print allows for serendipity to affect readers' thought patterns and habits, and the way platform algorithms and the cognitive processes of browsing result in echo chambers' magnification, is not complained about enough.

I'm going to speak from a cultural journalism perspective here, since I always feel out of my depth when talking politics. But yes, it was absolutely a big deal, as were alt-weeklies in general. I went from growing up on Long Island and reading the Voice, and, to a lesser extent, the New York Press, to college in Chicago and reading the Reader and New City. It was the place to find out about stuff before the Internet, and it certainly bested the proto-internet. With music at least, all the metadata-driven sites offering music listings out there are awful in varying ways; they're either tied up with corporate interests or just shoveling shitty data into an even worse package. The Voice was a niche publication to be sure, but it was a mass broadcast of what was happening to that niche. You don't see that today—I was in a car recently and I mentioned I'd seen Kanye West, and the driver was like, "What! Kanye West? I would have gone to that show."

And honestly, I've had the same thing happen with bands I like releasing records and touring, and I do this for a living. Online consumption of culture requires a sixth sense of knowing that something is coming down the pike. Papers like the Voice, even if you disagreed with what they covered in the edit well, at least offered pages and pages of ads for things that were coming up—for record shops, concert halls, dingy clubs, repertory houses, Off-Broadway theaters, etc. You could page through and at least get a sense of what was going on. Now? If you're reading about culture your de facto table of contents are either "most popular" charts or other articles related to what you're already reading about.

Foster Kamer, writer (2010)

It's almost surprising the print edition made it this long. That said, I think there's possibly a way for the Voice to succeed and exist in print, even though, let's be real, print is a luxury item everyone says they love but not nearly as many people use, in 2017, it just involves returning to far scrappier, less expensive, and slightly more niche roots, and reconstituting the operation with the paper's spirit intact.

Lisa Kennedy, features editor (1986-1996)

When you're in your 20s and early 30s and working with a group of people like that … heavy shit was going on. Reagan was president when I got there. AIDS was happening as the pandemic in the U.S. while I was there. My brother passed away from AIDS while I was there. The Voice was my family in some ways. Not that that's great. Who wants to have Oedipal conflicts at home?

I had a very moody day yesterday. I was in a little bit of mourning. In part because, it's not so different than having worked at the Denver Post, there's still a lot about print I believe in. It's frustrating and hard and head-scratching, even though the Voice isn't going away-away, there's definitely a sort of end of an era that has to do with a vital cultural institution.

It was absolutely the transformative experience of my journalism career, because of the people I was working with. The level of intelligence and engagement and all those things. But it's not like we all got along! It wasn't all Kumbaya. The hard news side could be rude to the cultural critics, and our cultural critics were extraordinary. Jack Newfield might say Cynthia Carr covering Karen Finley was a waste of newsprint. The tensions that exist in the world were also there, but I think that suggests the possibilities for how tensions can, not be ameliorated, but exploited for the best quality journalism.

One of the great packages that the Voice did that I think has held up was the one around the Central Park jogger rape—reporting pieces, political pieces. It was a great package. And our coverage about our current president when he was businessman and the stuff that Wayne did. It was an extraordinary place. It's always your Voice that was the really good one.

I think New Yorkers will notice. I think there are a bunch of people that maybe don't give a hoot. That's too bad, because I think you keep wanting journalism and alt-journalism to be vigorous. And you want young people, because we're always gonna blame the next generation—we want millennials to realize why a vigorous alt-press is important.

Harry Siegel, columnist (2011)

There was plenty unique about the Voice, little unique about a legacy print operation shutting down in 2017, and after a long run of decline and increasingly lousy owners. I got to write fully in my own voice for the first time, and it was my first chance to write a column about NYC, which I've been doing for the last four years for the Daily News. I mean, I turned down a job paying twice as much for a much bigger outlet because, you know, this was writing about my city for the Village Fucking Voice.

What made it unique depends a lot on the age of who you're asking. It was a very different paper in different decades. It was valuable enough for a long time that people paid money to read it. After New York Press forced it go free, in part by picking up some of its voices, including Alexander Cockburn, it was on a clear slope to irrelevance, one accelerated by the internet and the disappearance of the classifieds that helped pay for the journalism.

Araceli Cruz, senior associate editor (2007-2015)

When we were leaving, going from the office in the East Village to the Wall Street area, we were getting rid of so much shit in the office. There was this rolodex that was passed down from different employees. The person who owned it gave it to me when she left and I still have it. It's great, it has numbers of like Andy Warhol and all these amazing people in it. To me it's my own little piece of history.

I think one of the coolest moments I had was working along Michael Musto and Lynn Yaeger, they were these huge entities and part of this legacy. They didn't really know who I was at all, but one time I was in an elevator with Musto, and I had been there less than a year. I was literally freaking out. I looked up to them so much.

I always felt like I was on the optimistic side. Everybody I was friends with at the Voice had so much bitterness for a lot of stuff they went through. For me it was different because it was my first job moving to New York, so overall I loved it. There were obviously good and bad times. I think one of the worst parts was realizing my pay scale was really lower than low. And not realizing that because I never talked about it. I had to justify that. Do I ask for a raise and get denied or just keep doing my work and try to make the most of it? It was hard sometimes. I was probably the only Latina on staff for a very long time. Normally didn't care as much, but I did when I was the only Spanish-speaking person. I wish they would have viewed my skills a bit more.

Whenever there's any news about the Voice, new owners or editors, I really get sad when all these people talk shit. You still have to give it its props. Yeah, we are treated shitty by management, but I don't know any media company that isn't shitty to work for. I feel like it's just evolving into this new thing. I don't like that people are saying it's dead. It's just evolving. That happened to Rolling Stone when they had a bigger issues and went small. It's just a part of this industry. I feel more for the people that are working there now. They're entering the Voice the same way I did, wanting to be part of this legacy.

Management has always been shitty toward the papers ever since they got bought in 2010 I guess it was. But the paper has always had its own life and the staff has been why it survived mostly because of the union. To me that would be more of a shame if they disbanded the union. That's the only reason I was there for so long. They provided so many different ways for me to live. Healthcare and all that. I'm more concerned with that than the paper. Honestly, I didn't really pick up the paper after a while myself. I feel like everyone is online regardless. If that's gonna keep it alive I think it's fine.

Robert Christgau, music writer (1969-2006; 2016-present)

I'm disappointed. I don't like it when any print publications folds and this is one with whom I had an old relationship and had been writing for occasionally in the past as well. I'm not happy about it at all.

I think the [loss of the] Voice has symbolic weight. I'm not entirely convinced that print on paper periodicals are going to die. Ten years ago everyone believed that the Kindle was going to kill the book. It didn't. Walk into the Strand Book Store. Books are not dead. I'm 75 years old, reading the New York Times every day since I was 20. I assume there are people that are better with a mouse and linking to shit than I am, I just don't believe it gives you the same amount of autonomy. So I'm not happy about it.

The Voice Union, they did this letter, and I signed the letter and tried to get other people to sign. I'm a believer in unions. The Voice has been unionized for 40 fucking years, that is a very substantial amount of its total life. I was active in the union. I tweeted about the fact that union negotiations would be resuming today, and this isn't what I wanted to hear. I assume, it's still a publication, I can see no reason why it isn't still unionized. My attitude is: to the fucking death.

Yes, you could make a decent living when I started out. I can't see any way in which the web doesn't permanently decrease the cash value of the written word. It increases the amount of writing to reading by a factor of 10? 20? 100? I don't know what the numbers are but they're huge. I believe there will always be people who know quality, but for sure it's leached a lot of the cash value from the written word.

The reason I wrote for the Voice was I was always able to do what I wanted to do. I have that kind of freedom certainly at Noisey. That's always the way I wanted it to be. I never had any regrets about making that the place I worked. It was a great place and perfect for me.

Luke is a writer from Boston who writes the newsletter Welcome to Hell World and author of a book of the same name.