Ancient Earthquake Turned Mosaic Workshop into Time Capsule

An earthquake-toppled house in the ancient city of Jerash is providing archaeologists with clues on how artisans constructed mosaics during the eighth century.

The ancient house was likely undergoing a remodel when, on Jan. 18, 749, the massive earthquake struck Jerash, located in what is now Jordan, the researchers of a new study found.

Before the earthquake, artisans were putting together mosaics for the floors of the house, but they abandoned their artwork after the natural disaster struck. This abandonment turned the house into a time capsule, allowing modern-day archaeologists a chance to see how artisans from the Umayyad — the early Islamic period — assembled these decorative mosaics. [Photos: Lost Roman Mosaics of Southern France]

"It offers a unique glimpse into the moment in time immediately before the earthquake struck," the researchers wrote in the study.

House of the Tesserae

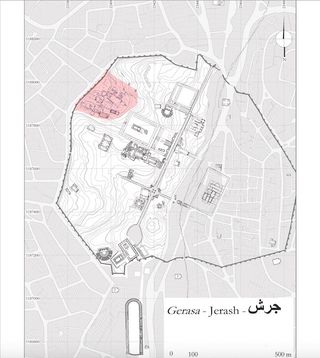

Archaeologists have already combed through much of Jerash, an ancient walled city that flourished from the first century B.C. through the middle of the eighth century A.D., when the earthquake struck.

However, two archaeologists realized that areas within the highest part of the city, located in the northwest quarter, had yet to be studied. In particular, an extravagant house with partially completed mosaic floors caught their attention.

They dubbed it the "House of the Tesserae," named for the individual tessera pieces that make up its mosaics. The house was likely owned by wealthy people, as it had several rooms surrounding a courtyard, where a rainwater-collecting cistern sat hidden underground. The house also had a porch lined with Roman-style Corinthian columns, said study co-researcher Rubina Raja, a professor of classical archaeology at Aarhus University in Denmark.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The top floor of the two-story house had tumbled onto the ground floor — likely because of the violent earthquake, Raja said. But, curiously, both floors were barren of all furniture and daily objects, suggesting that the owners had cleared out the house for a remodel, Raja said.

"What we found in there was the preparation for new wall paintings in the house, and then these new mosaics that were about to be laid," Raja told Live Science.

The floor of the upper level was already adorned with large mosaics — all geometric in pattern, meaning they didn't show a specific scene — indicating that the house was structurally sound, at least before the earthquake hit, Raja said.

"Mosaics are heavy things," she said. "They're small stone cubes, but they are all set in mortar and a sort of plaster to be kept in place. So, in total, they become extremely heavy."

Distinct finding

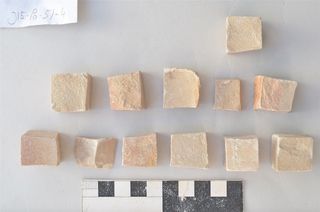

On the bottom floor, the archaeologists found troughs filled with "thousands and thousands of mosaic tesserae that were pristine, unused and ready to be laid in a larger mosaic," possibly on the ground floor, Raja said.

Those tesserae-filled troughs suggested that the mosaic pieces were made on-site, she said. Until this finding, researchers were unsure whether ancient artisans crafted the tesserae in permanent, off-site studios or on-site. [Photos: Ruins of Mysterious Wall Found in Jordan]

"What our findings now indicate is that these tesserae were indeed most likely produced on location," she said. "You would have the craftsmen or craftswomen who actually carved these tesserae on-site to be used later."

Moreover, the "tesserae were not just thrown on a heap, but they were carefully stored before they were used," said study co-researcher Achim Lichtenberger, a professor of classical archaeology at the University of Münsterin in Germany.

The researchers also found the skeletal remains of a young person, who was likely trying to exit the house when the earthquake hit. It's possible that a metal hammer found near the body was used to produce the tesserae, which were made of white limestone, pinkish limestone and a black stone that has yet to be identified, Raja noted.

"We're not completely sure it was used for this, but the fact that it was found close to the trough with all of these white tesserae in it, inside a house that's otherwise swept for objects, does indicate that there might be a relation between the tool and the tesserae," she said.

Abandoned quarters

Archaeologists have dated more than a million pottery shards from the northwest quarter of Jerash over the past six years, and none of them date to the period after the earthquake. It wasn't until the 12th century that people returned to the area, Raja said.

It's possible that any survivors from the northwest quarter moved to Jerash's main streets, she said. Perhaps, despite "the richness of these houses, the catastrophe was so devastating there was not enough means, or enough manpower, to actually rebuild the complete city after the earthquake," Raja said.

The study was published in the August issue of the journal Antiquity.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.